As a dog lover, I’m not alone in believing these creatures have important knowledge to pass along to us humans. With this in mind, I want to discuss how aging affects your body and bring to your attention some recent evidence from the scientific literature on how stretching--and Downward Dog--can help.

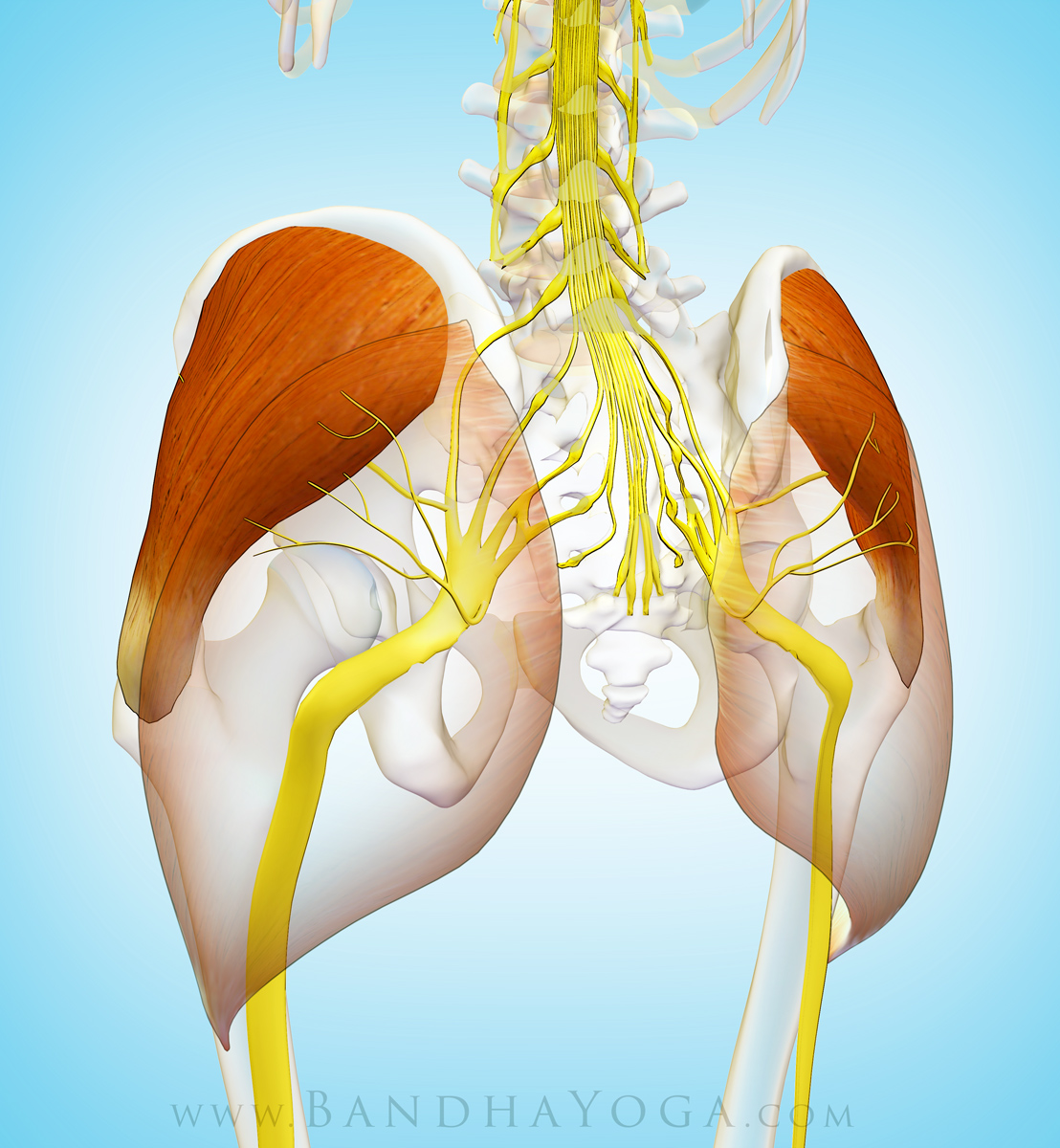

First, let’s take a look at reciprocal inhibition…Reciprocal inhibition is a biomechanical and physiological process whereby when we contract a muscle on one side of a joint, the muscle on the other side is inhibited from contracting. This takes place to varying degrees throughout the range of motion of a joint and enables us to do things like walking. For example, when you contract your tibialis anterior to dorsiflex your foot while walking, you automatically inhibit the calf muscles. This helps to prevent catching your toes.

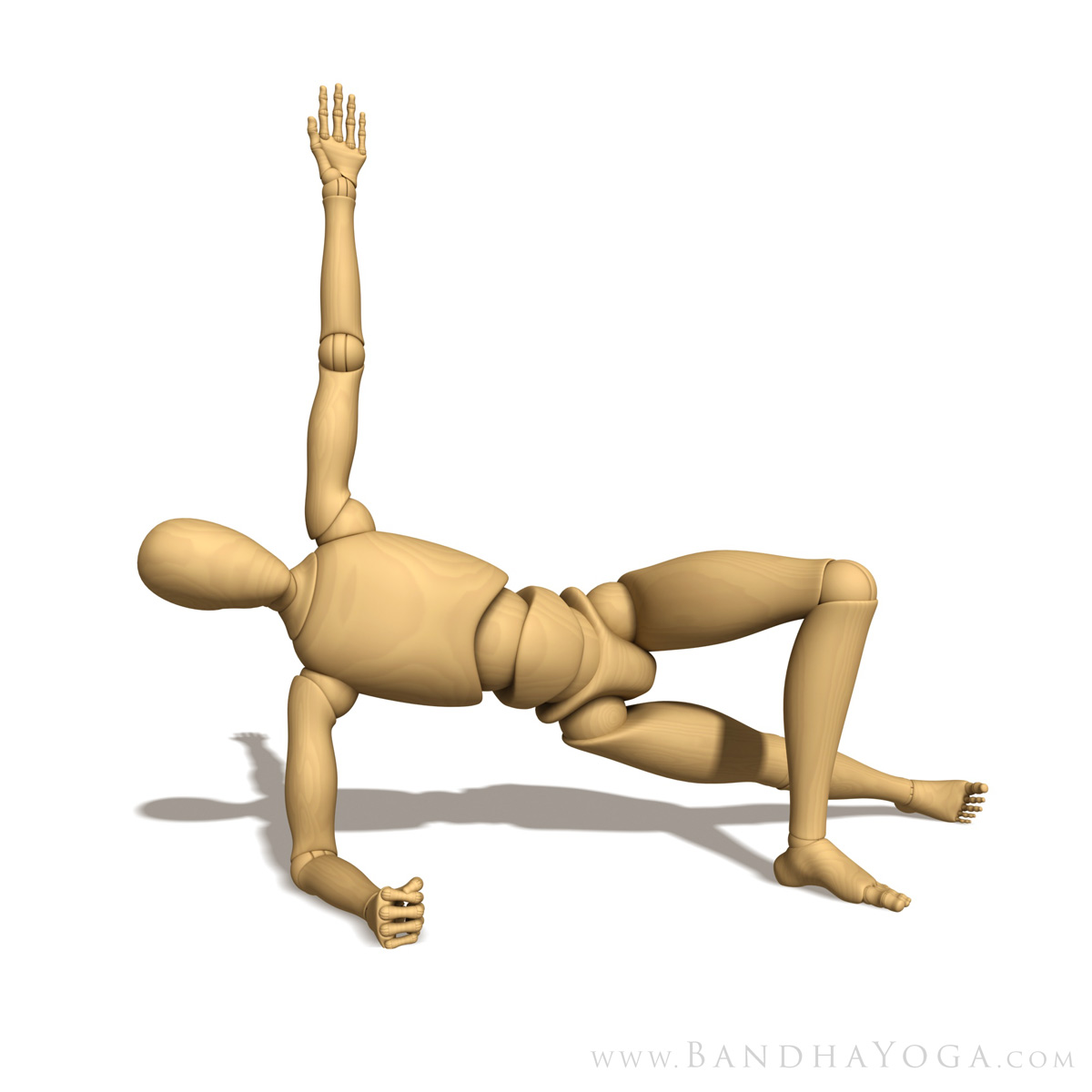

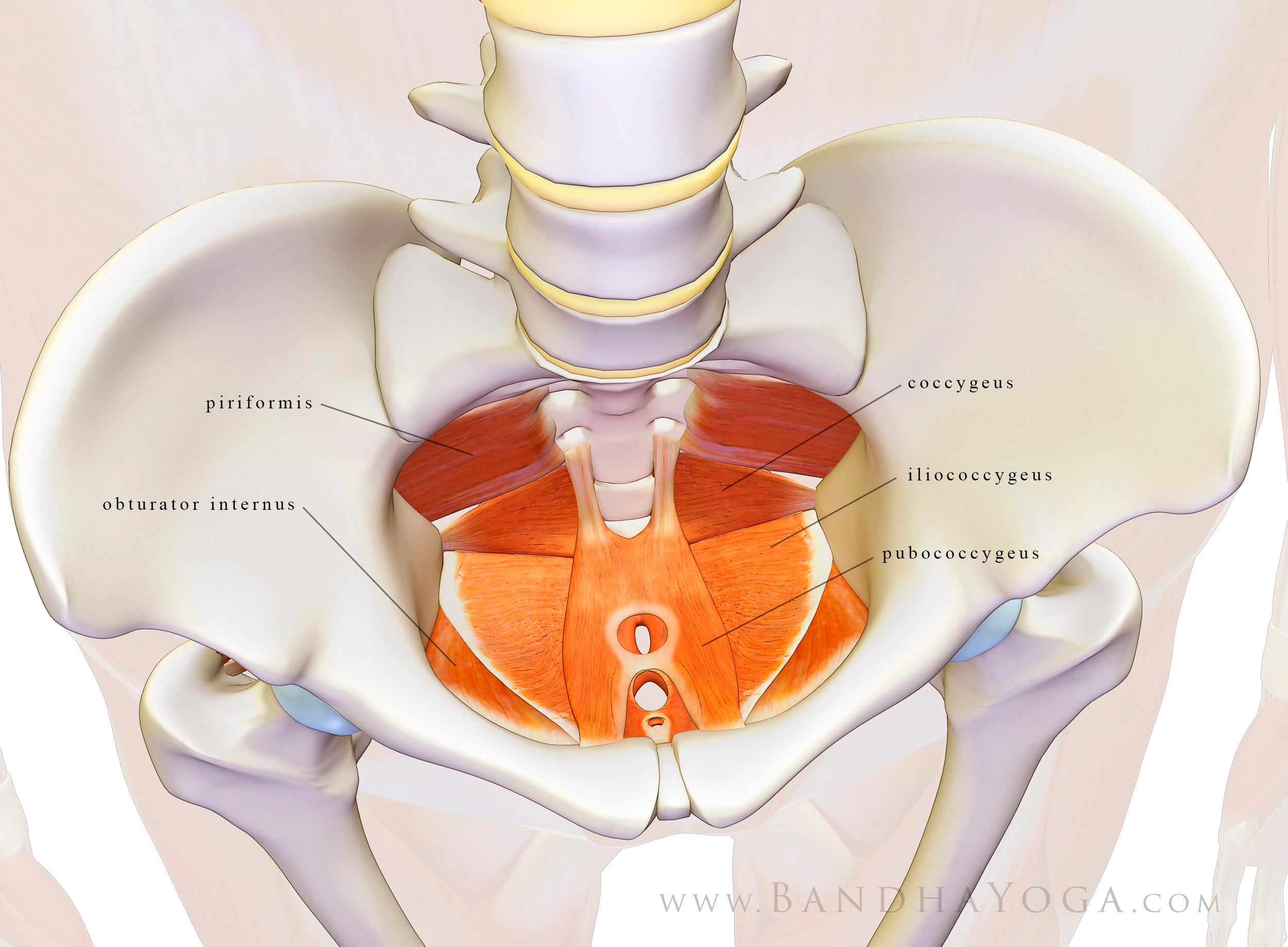

Reciprocal inhibition is controlled and regulated at the level of the spinal cord level and also the brain. Of course, as we reach the ends of range of motion of a joint, a process known as co-contraction kicks in to stabilize the articulation, thus modulating the inhibitory effect of the contracting muscle on its antagonist. In other words, we are not Gumby. (Most folks know this implicitly, but I point it out here to correct some confusing info from recent blogs on the subject of stretching and yoga). Figure 1 illustrates the agonist/antagonist pairs for the forward bend Paschimottanasana and the backbend Setu bandhasana.

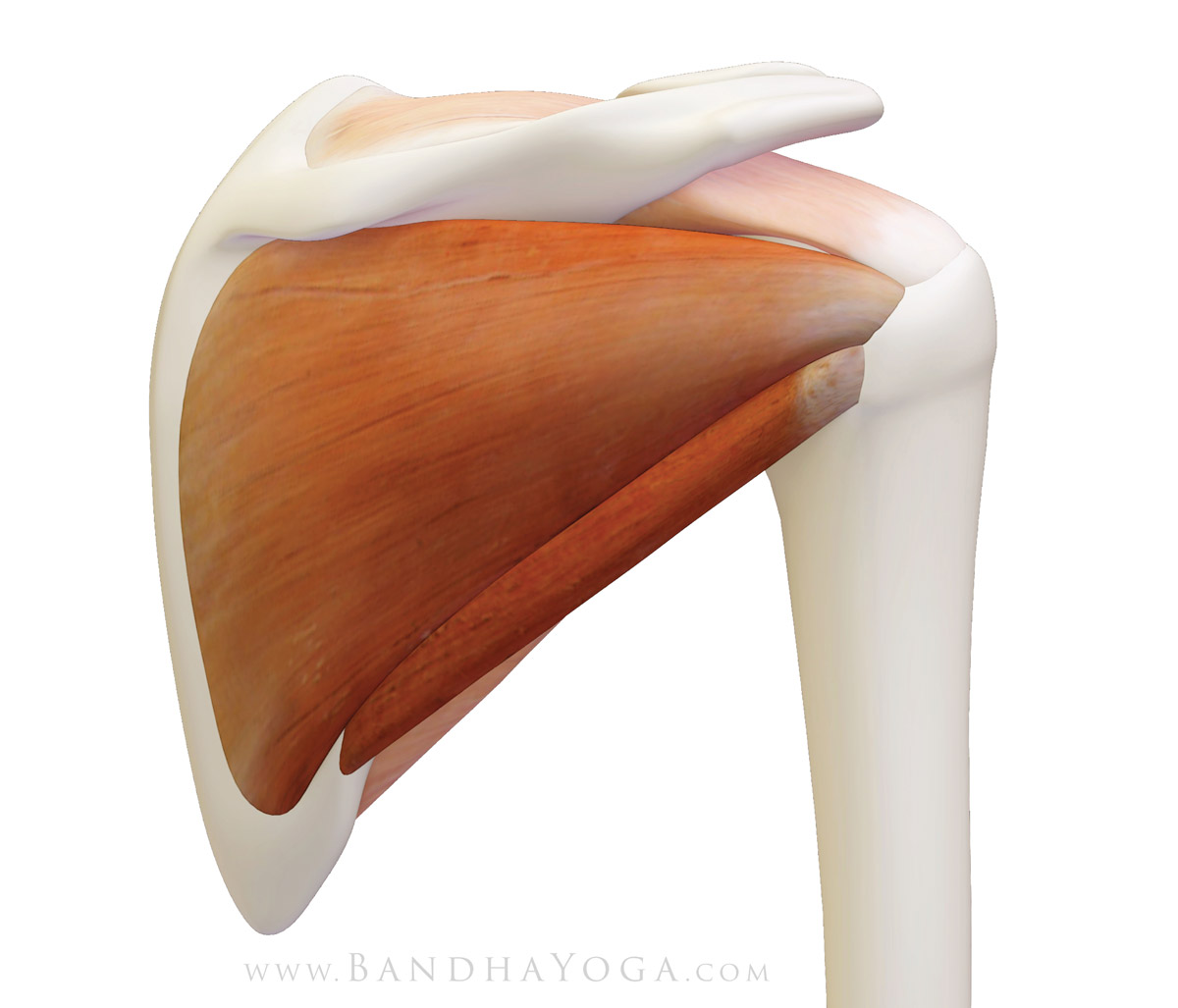

![]() |

| Figure 1: Agonist/Antagonist pairs in Paschimottanasana and active Setu bandhasana. |

What can happen as we age…Scientific studies have demonstrated that reciprocal inhibition diminishes as we age (and also in certain disease processes). This is particularly important for activities such as walking. For example, if the tibialis anterior does not efficiently inhibit the gastroc/soleus muscles of the calf, the person tends to catch their toes, stumble and fall. If that weren't bad enough, our bones also weaken with age, so falls can lead to fractures--especially of the hip. This puts the person in a hospital under the care of an orthopedic surgeon as so on…(a story I know all too well). So, methods or techniques that improve reciprocal inhibition could potentially benefit us as we age.

How stretching can help…Recent scientific evidence has shown that stretching can increase reciprocal inhibition between antagonist muscles. For this study, the authors investigated the effect of stretching on reciprocal inhibition between the tibialis anterior and the gastroc/soleus complex. They stated:

“In conclusion, we have found that 3 wk of twice-daily, static plantar flexor stretching resulted in a significant increase in RI, measured in soleus and gastrocnemius during voluntary, tonic dorsiflexion contractions.” (The full article is linked below in the references)

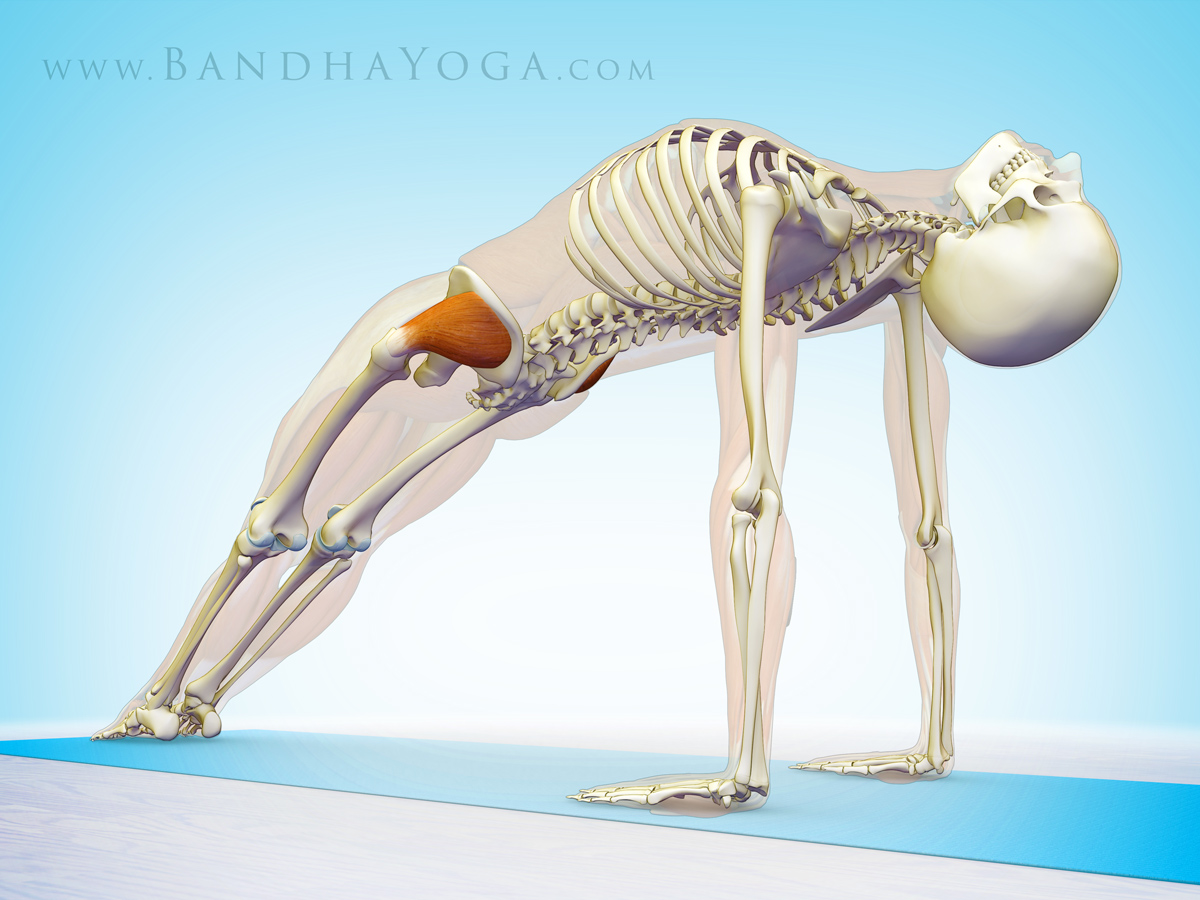

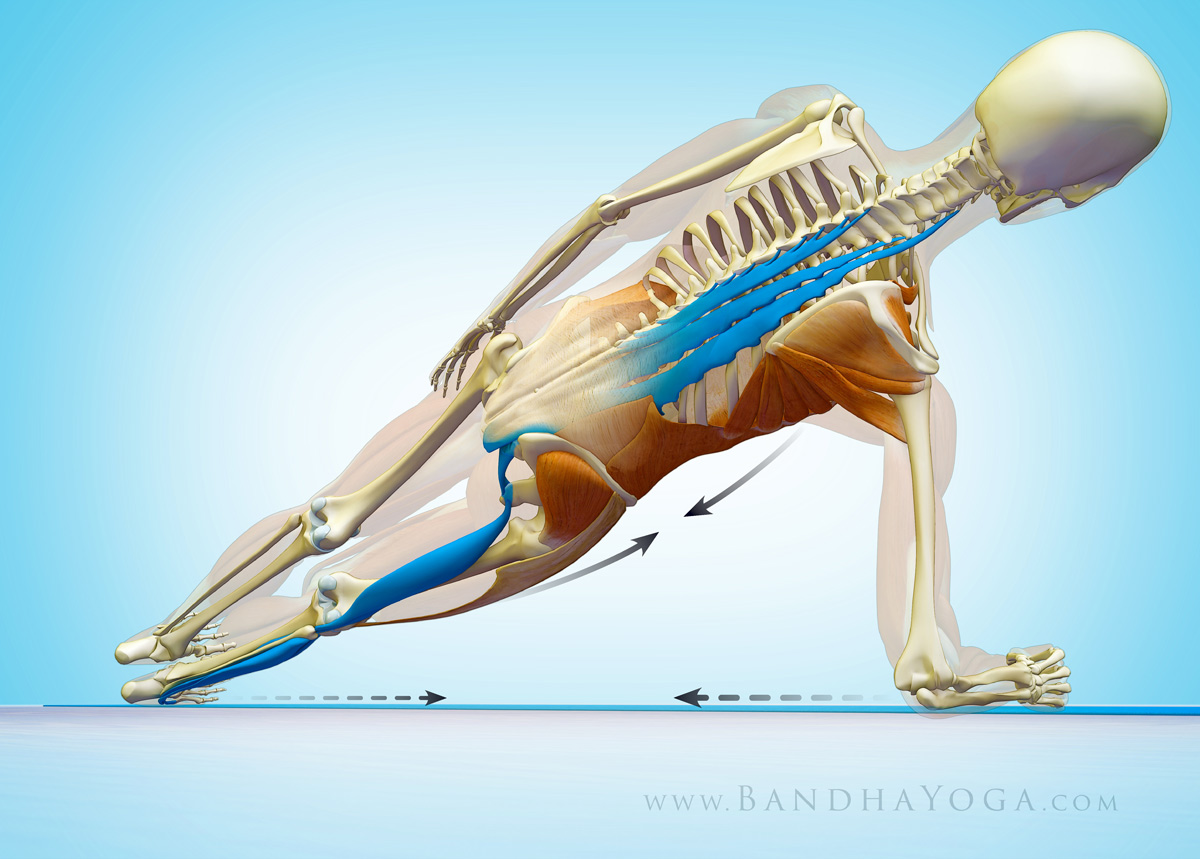

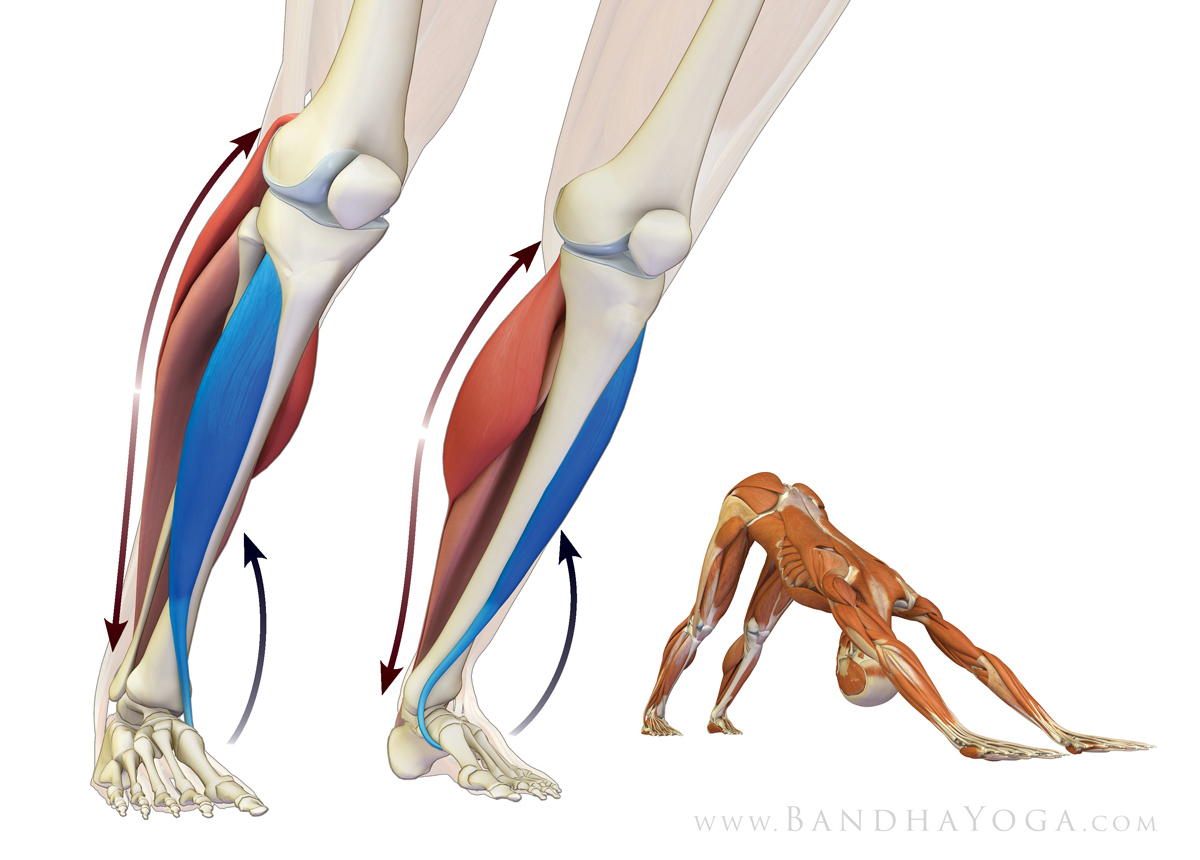

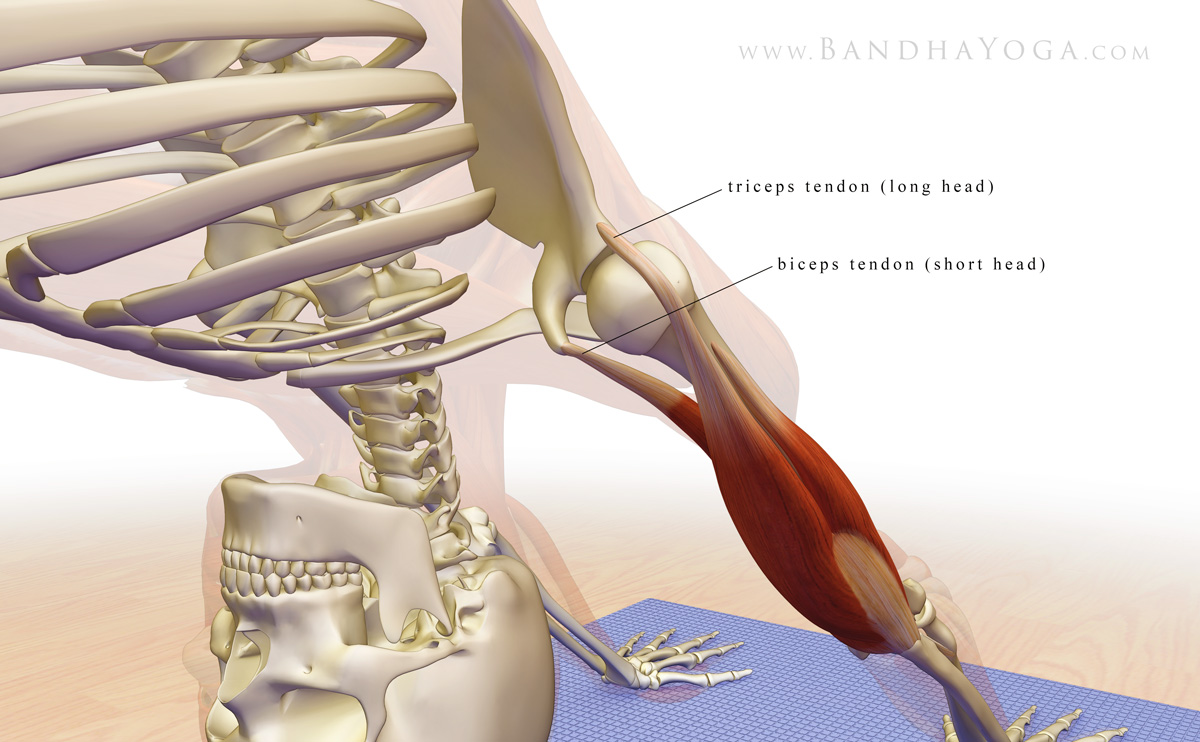

These are some of the same muscles we work with in Downward Dog. Thus, regular practice of this pose may help maintain reciprocal inhibition between the tibialis anterior and the calf muscles. For a tip on how to make this pose more efficient, take a read through

“A Tip to Help You Lower Your Heels In Downward Dog." This blog uses active stretching to improve flexibility of the gastroc/soleus muscle complex. I received a lot of positive feedback on it, so give it a go.

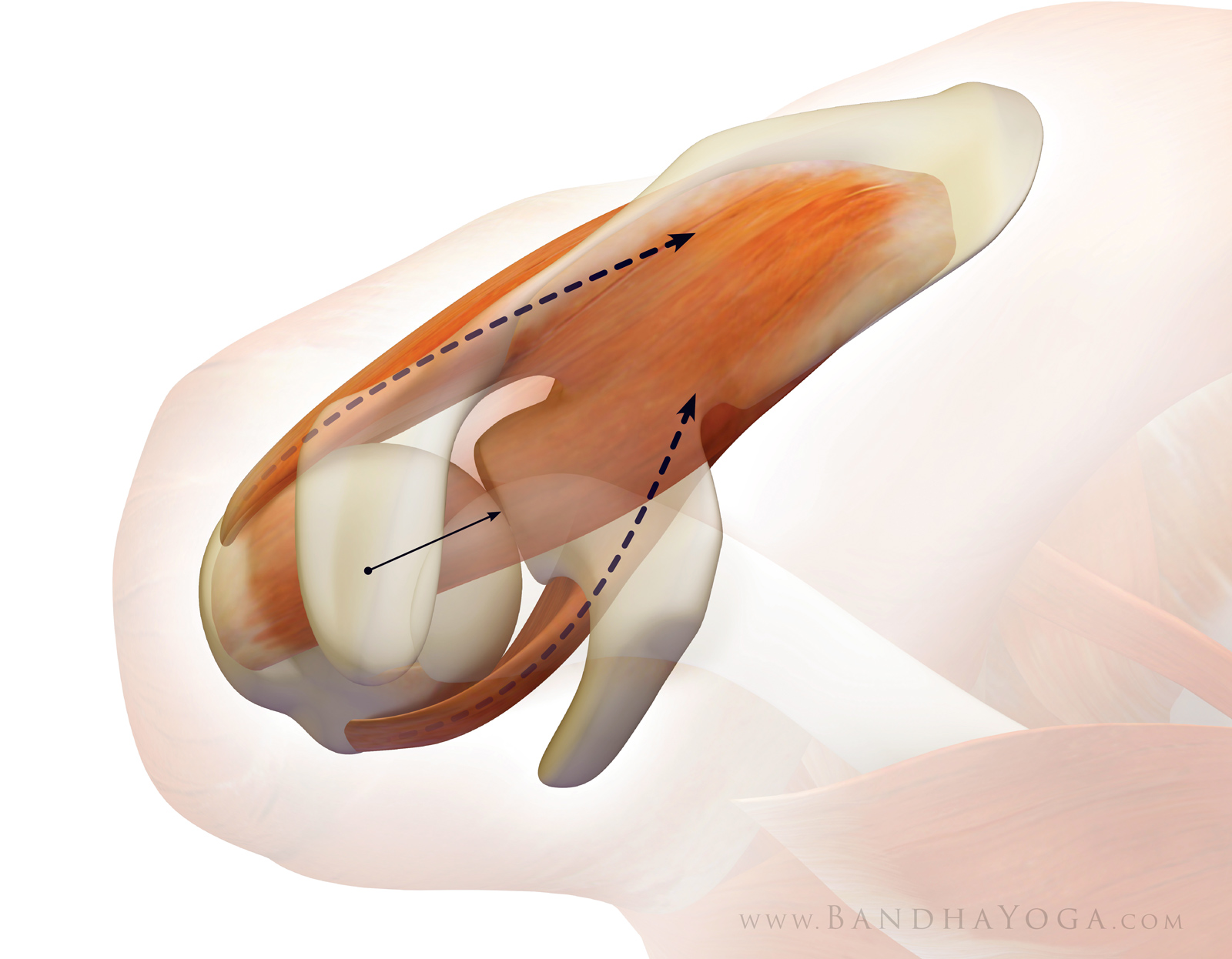

![]() |

| Figure 2: The tibialis anterior as agonist and gastroc soleus as antagonist in Down Dog pose. |

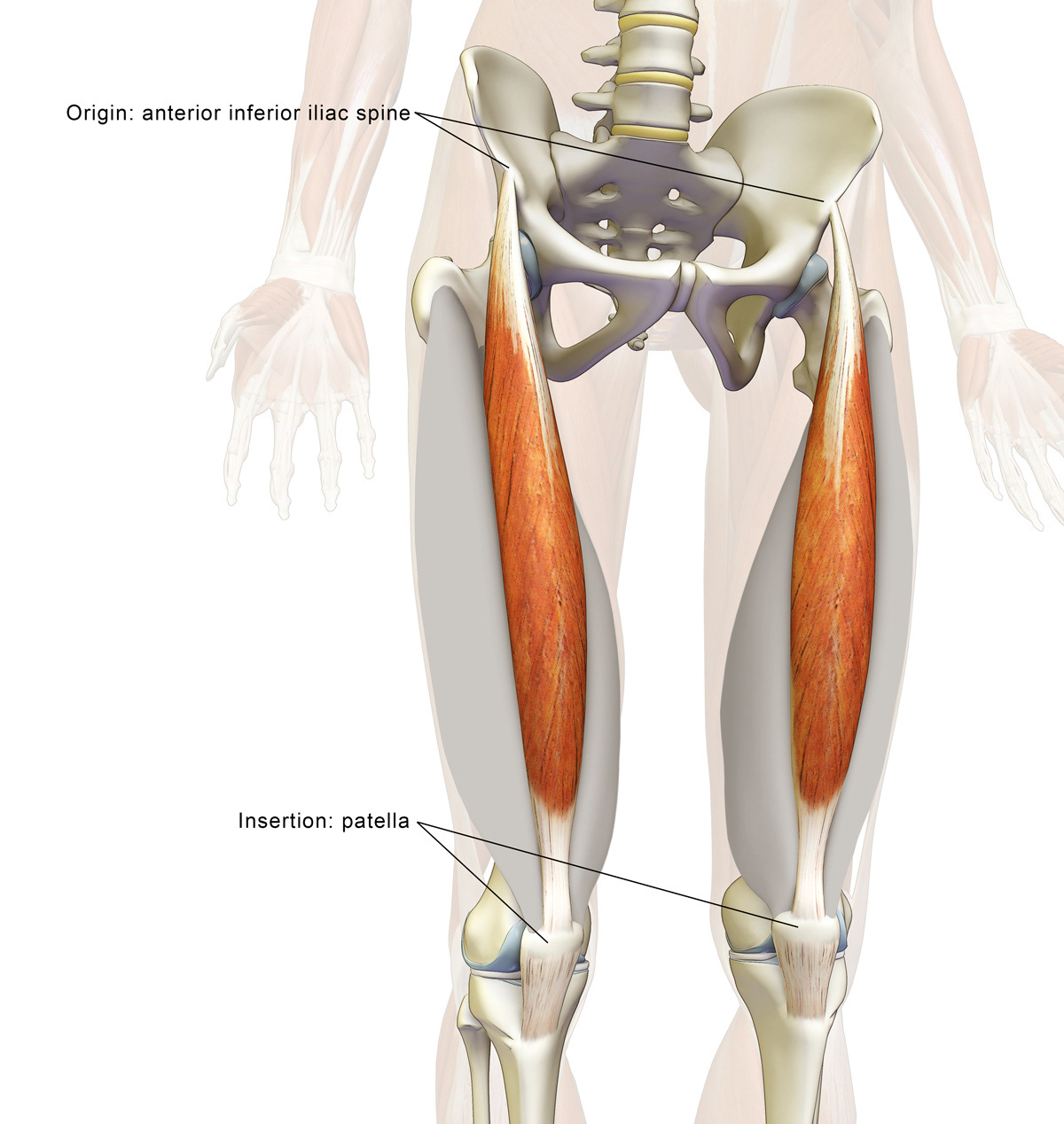

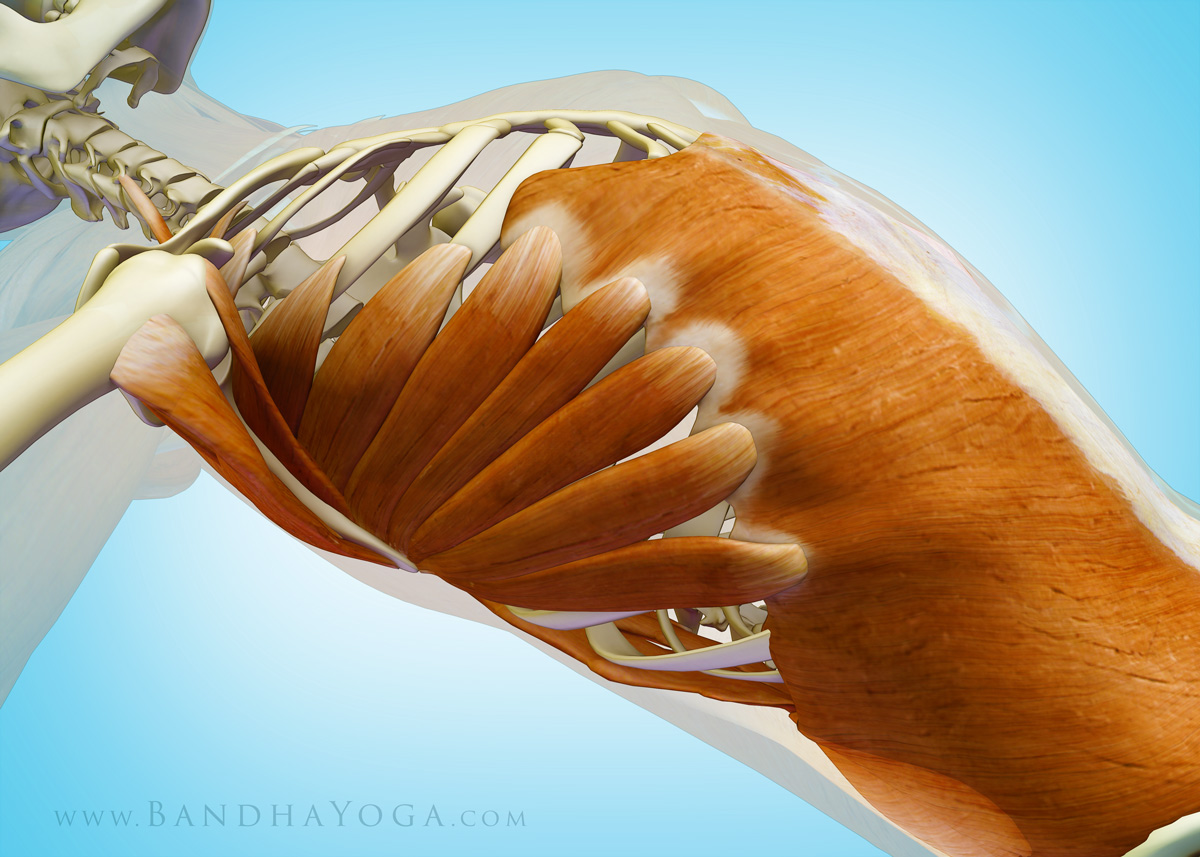

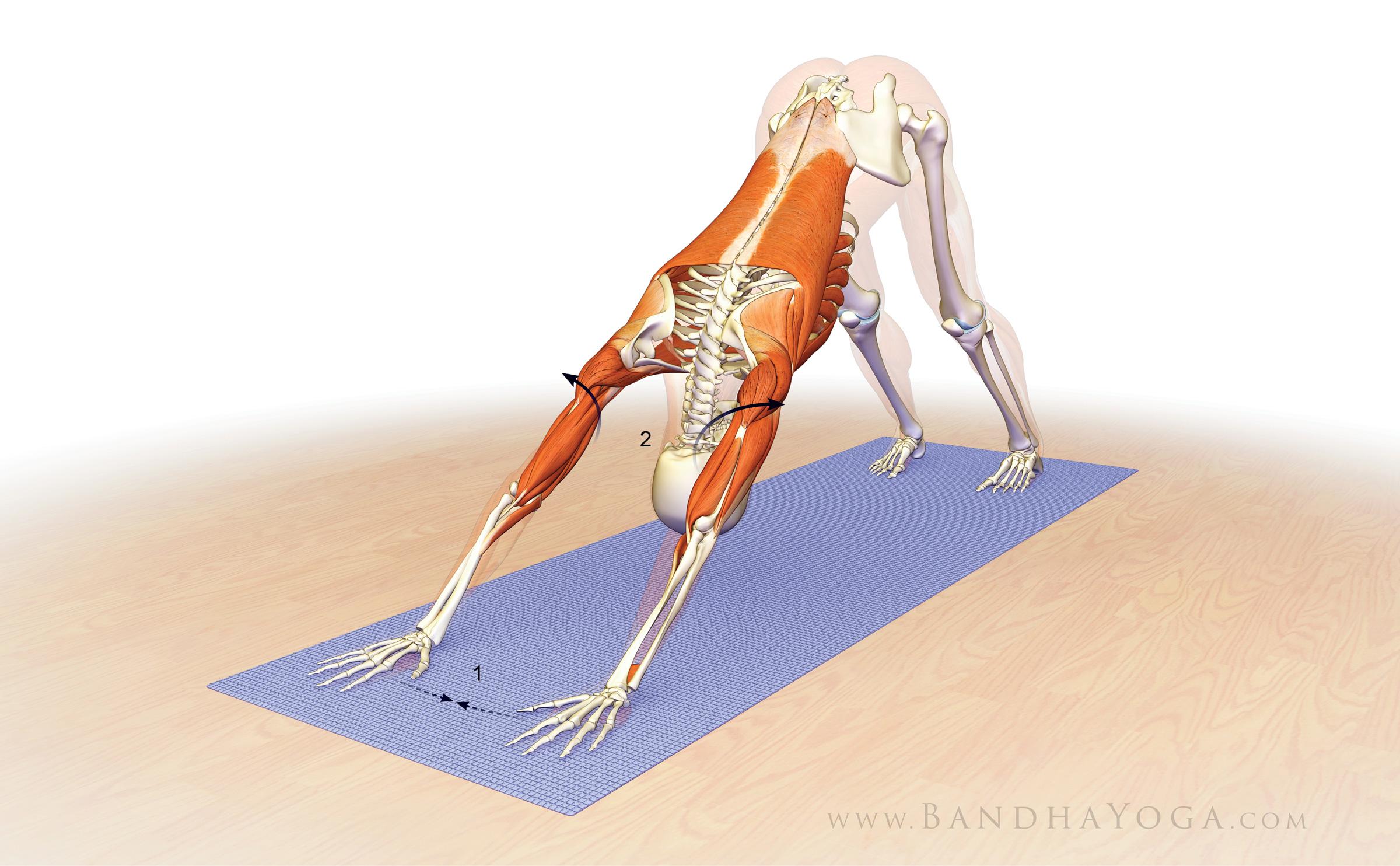

On Active Stretching…In active stretching, one improves muscle flexibility by contracting the opposing muscle group while stretching the target muscle. In the case of the hamstrings, this means engaging the quadriceps during the stretch. Shirley Sahrmann, PhD (Professor of Physiotherapy at Washington University School of Medicine) and others have advocated active stretching as a means of increasing muscle flexibility. It improves flexibility of the muscles on one side of the joint while improving strength and function of the muscles on the other side.

A recent article from the medical literature compared active vs. passive stretching of the hamstring muscles. The authors stated:

“Such an active technique is based on reciprocal inhibition between agonistic and antagonistic muscles.”And concluded:

“Active stretching produced the greater gain in the AKER test, and the gain was almost completely maintained 4 weeks after the end of the training, which was not seen with the passive stretching group. Active stretching was more time efficient compared with the static stretching and needed a lower compliance to produce effects on flexibility.” (AKER=active knee extension range of motion)

This makes sense to me from a yoga perspective as well--keeping in mind that there are many different ways to climb the mountain. Improving muscle flexibility is only one of the functions of asanas. Active stretching, among other benefits, improves your mind/body connection, alignment of your joints and your mental focus. Improved focus in turn helps to identify and correct imbalances.

Click here to read more on the subject of muscle imbalances.

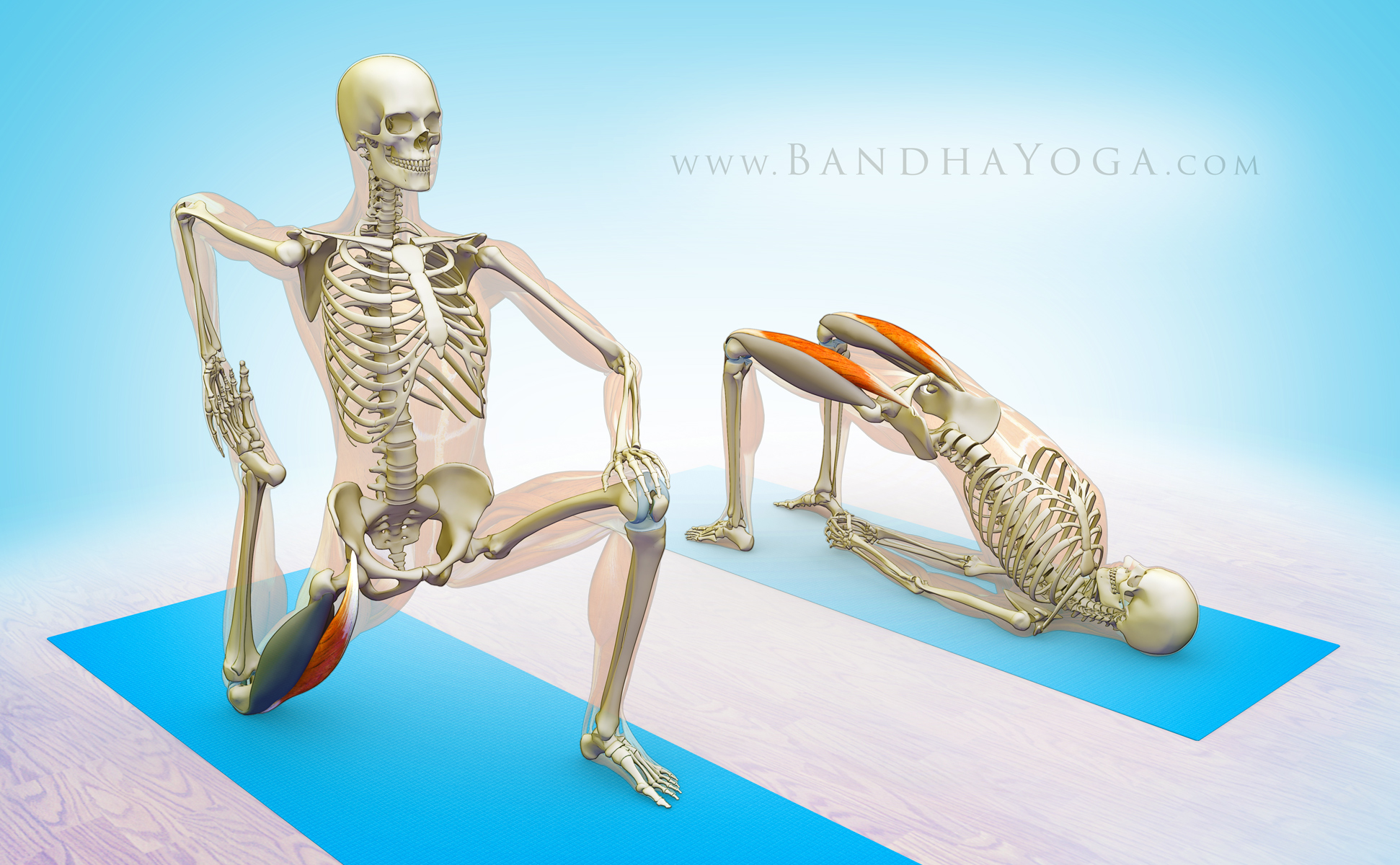

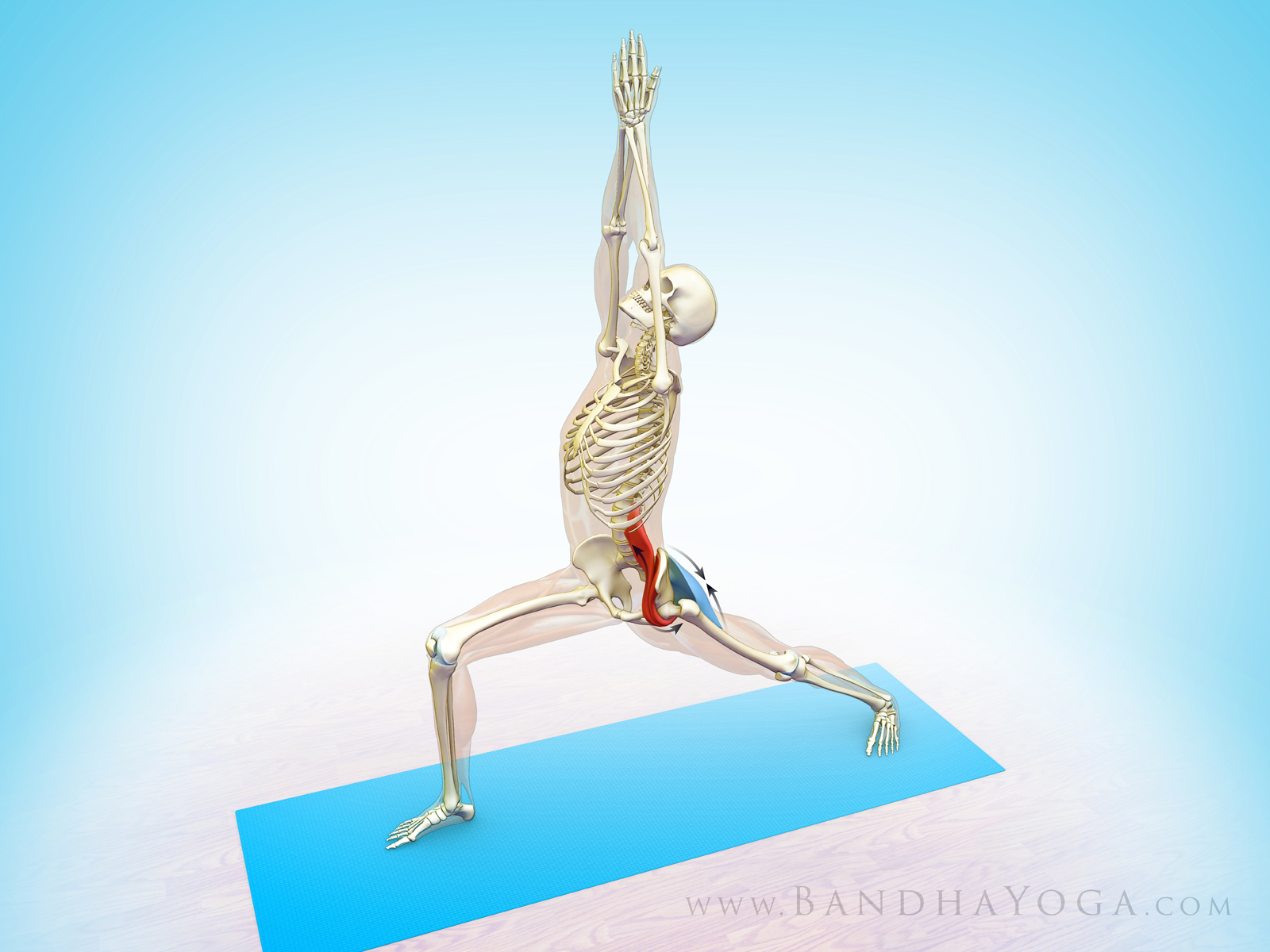

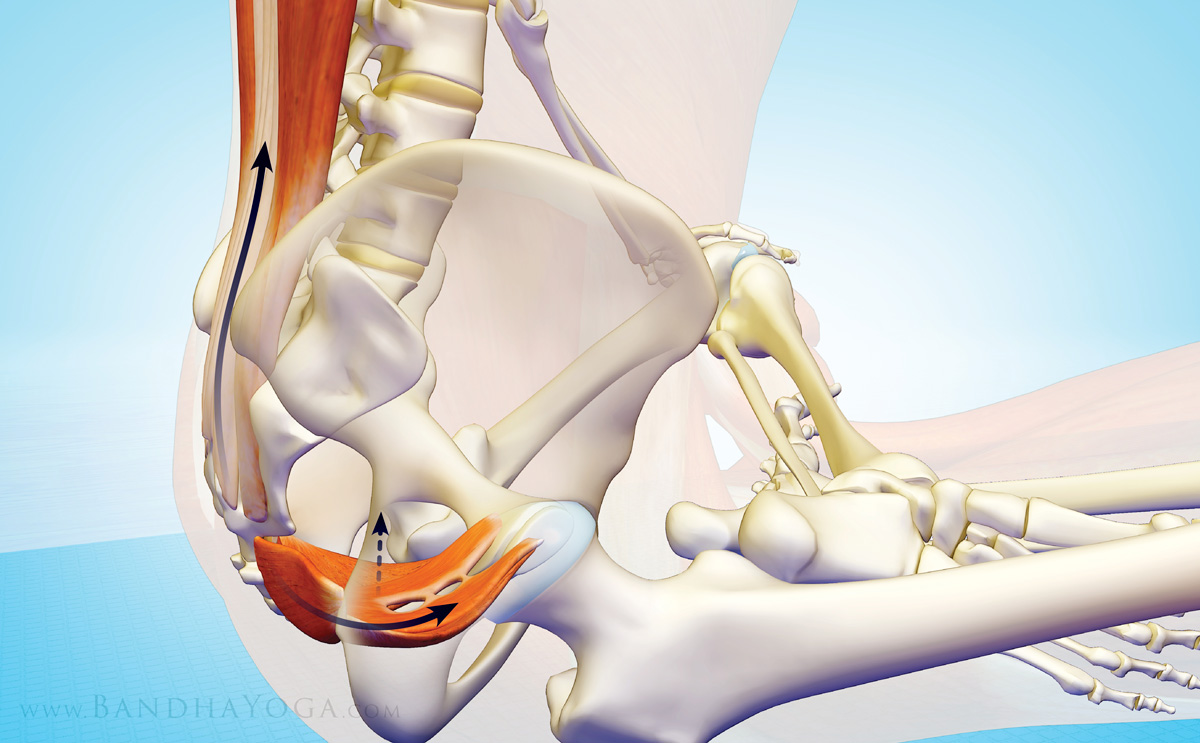

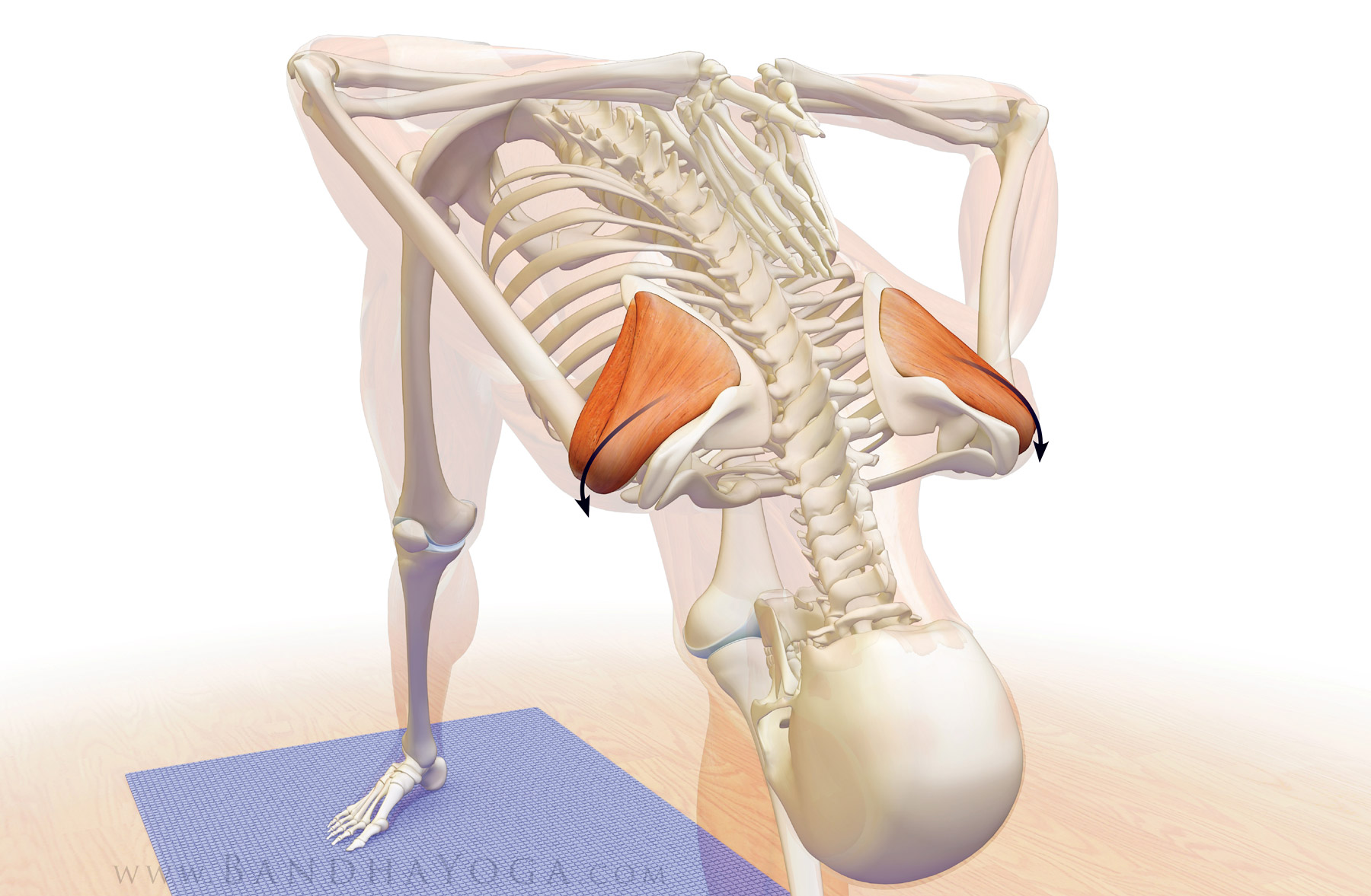

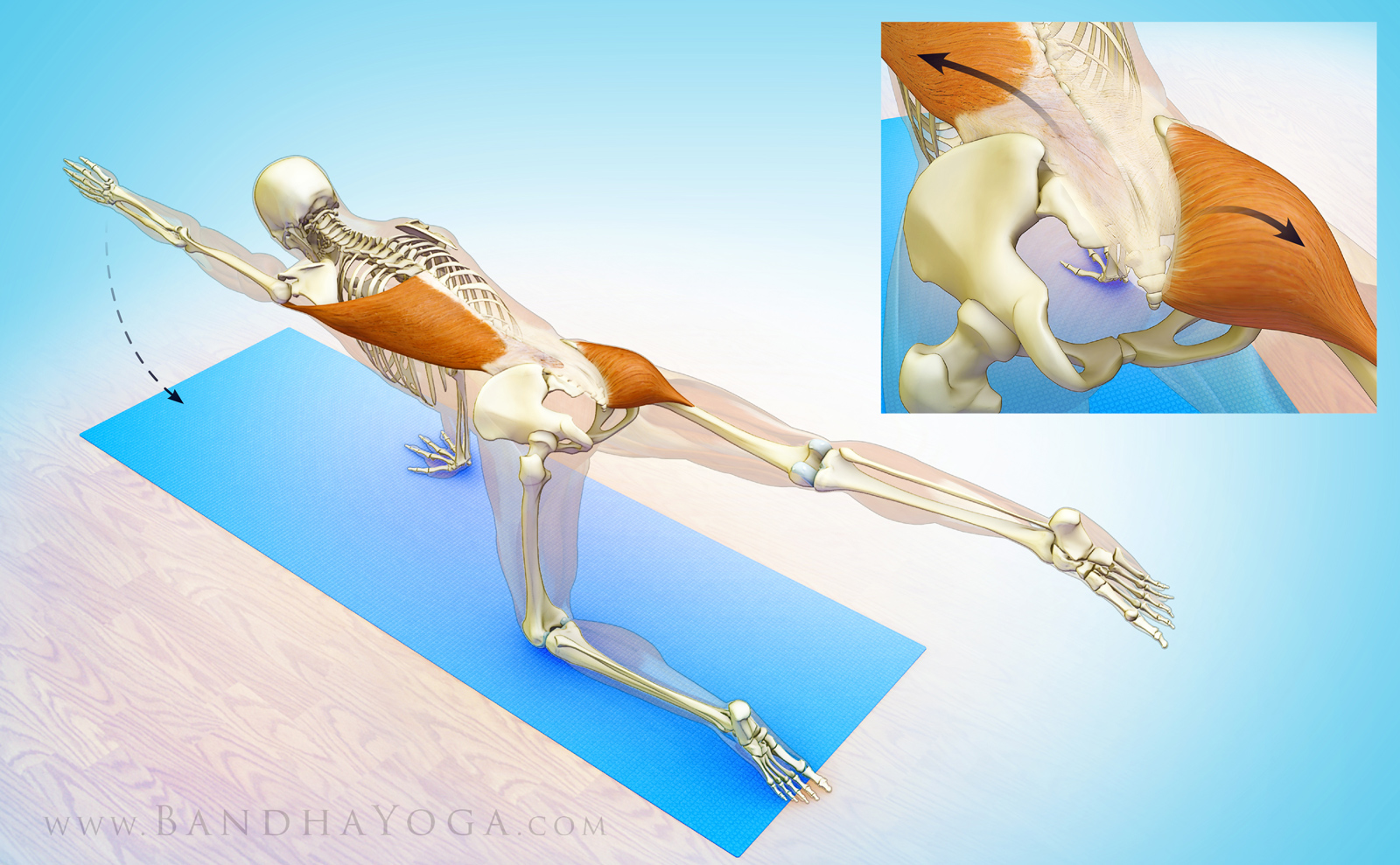

![]() |

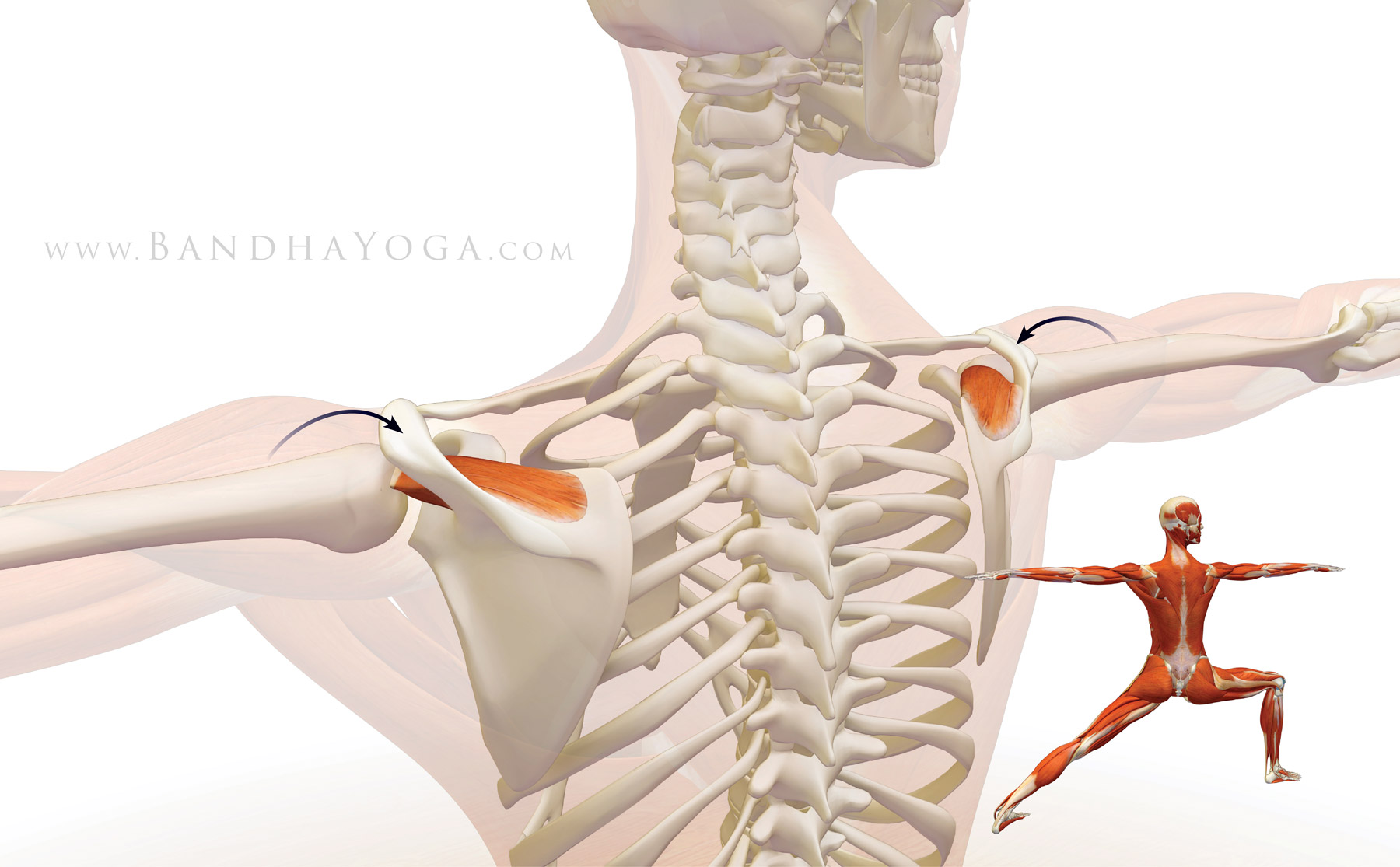

| Figure 3: An agonist/antagonist pair in Warrior I (gluteus maximus and illiopsoas). |

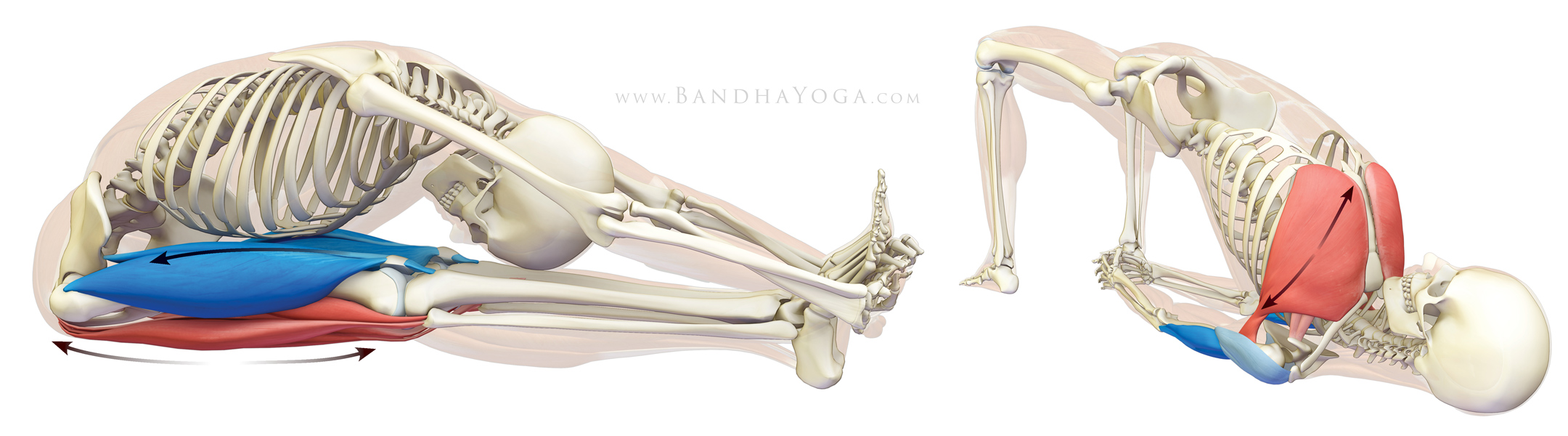

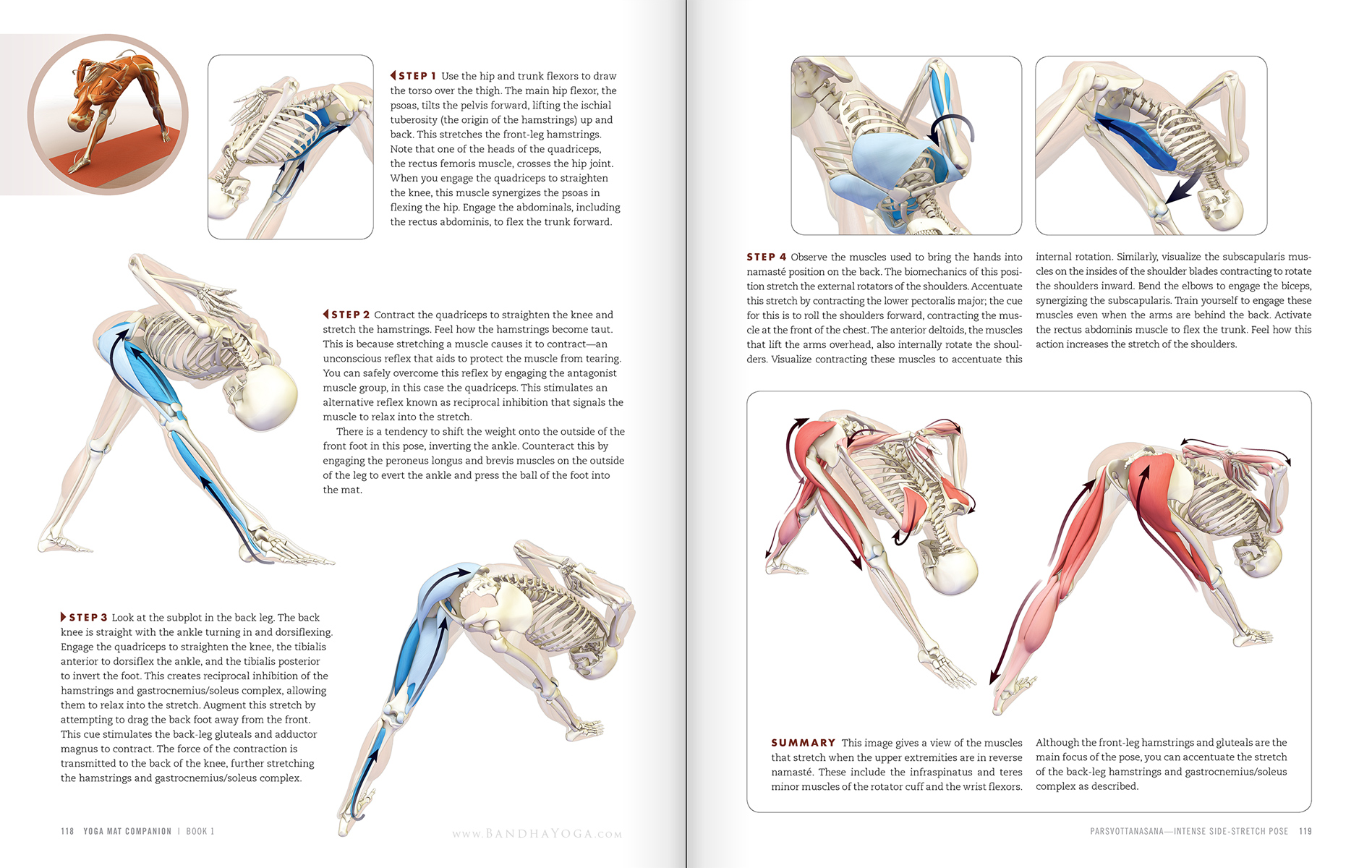

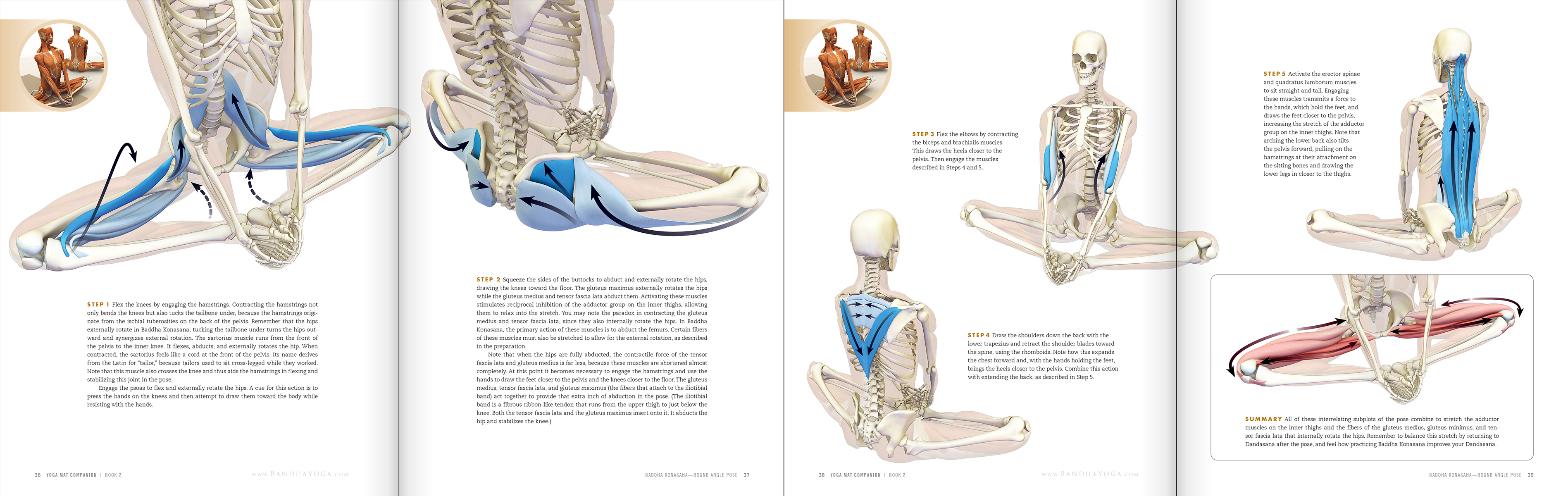

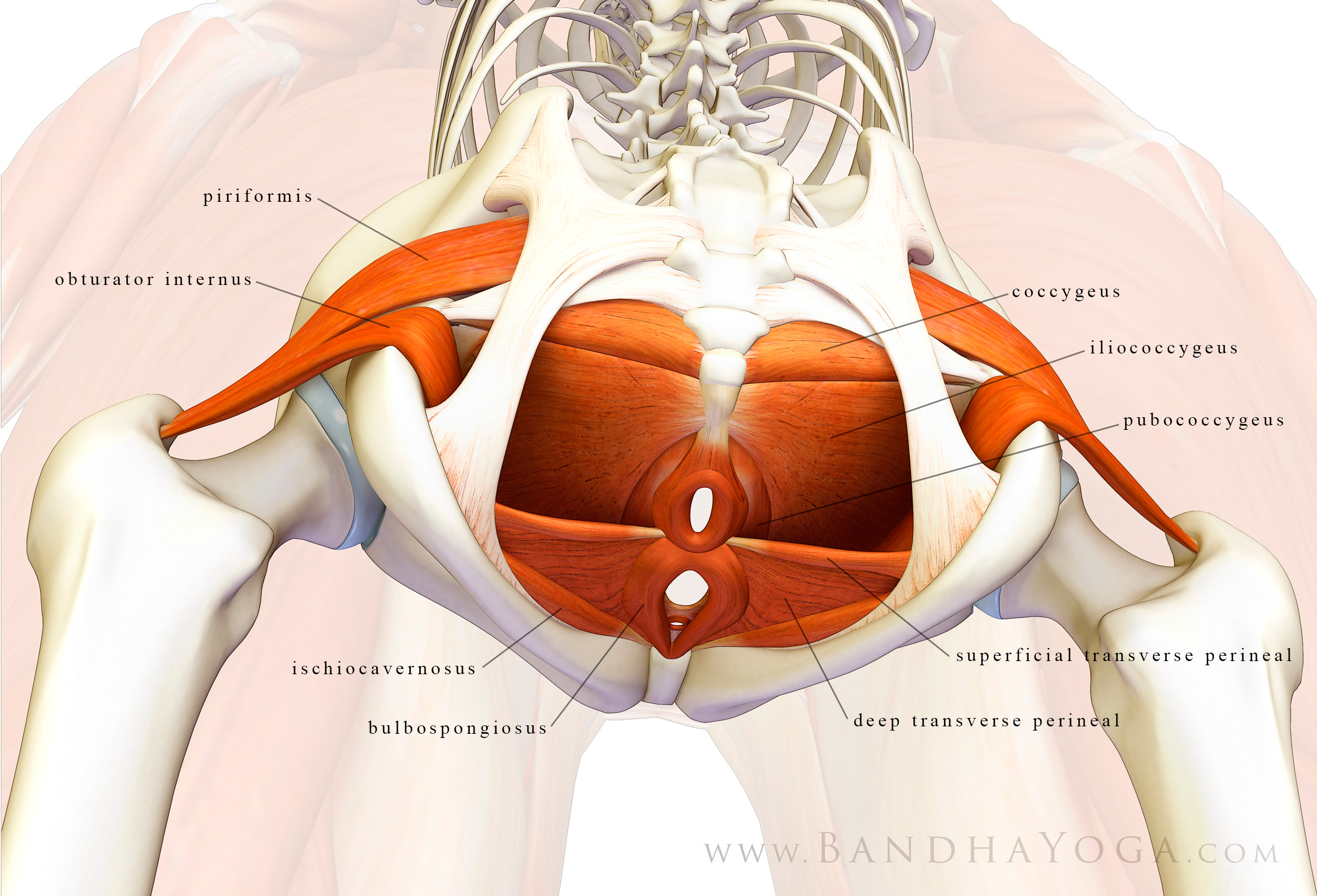

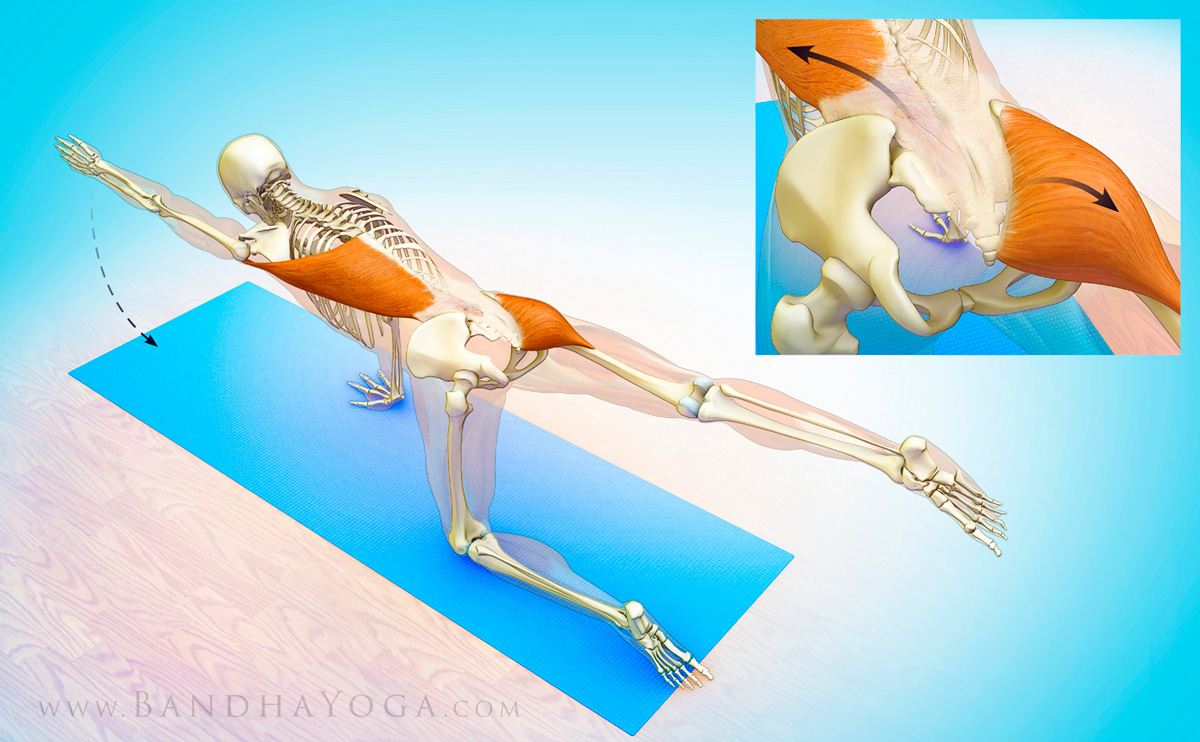

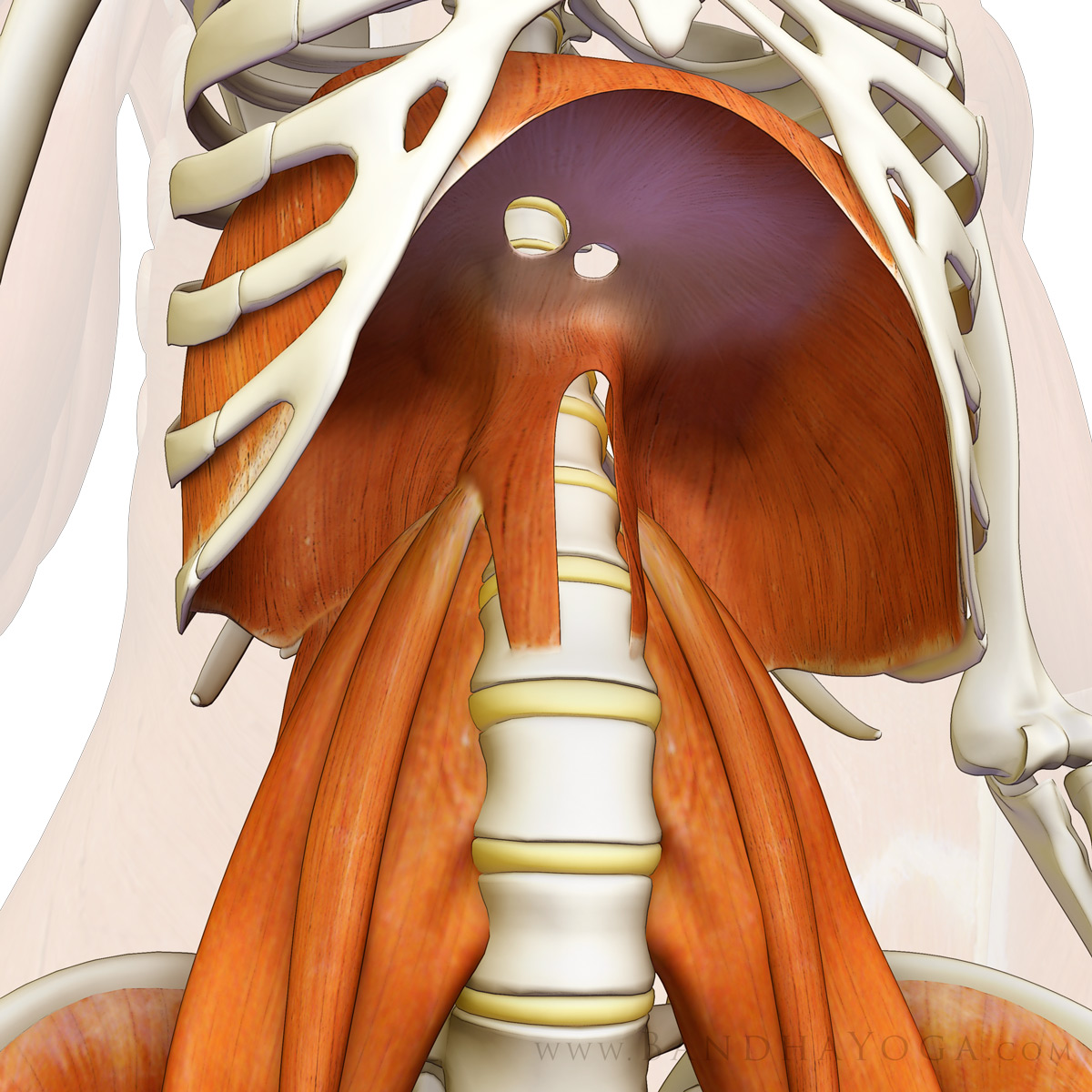

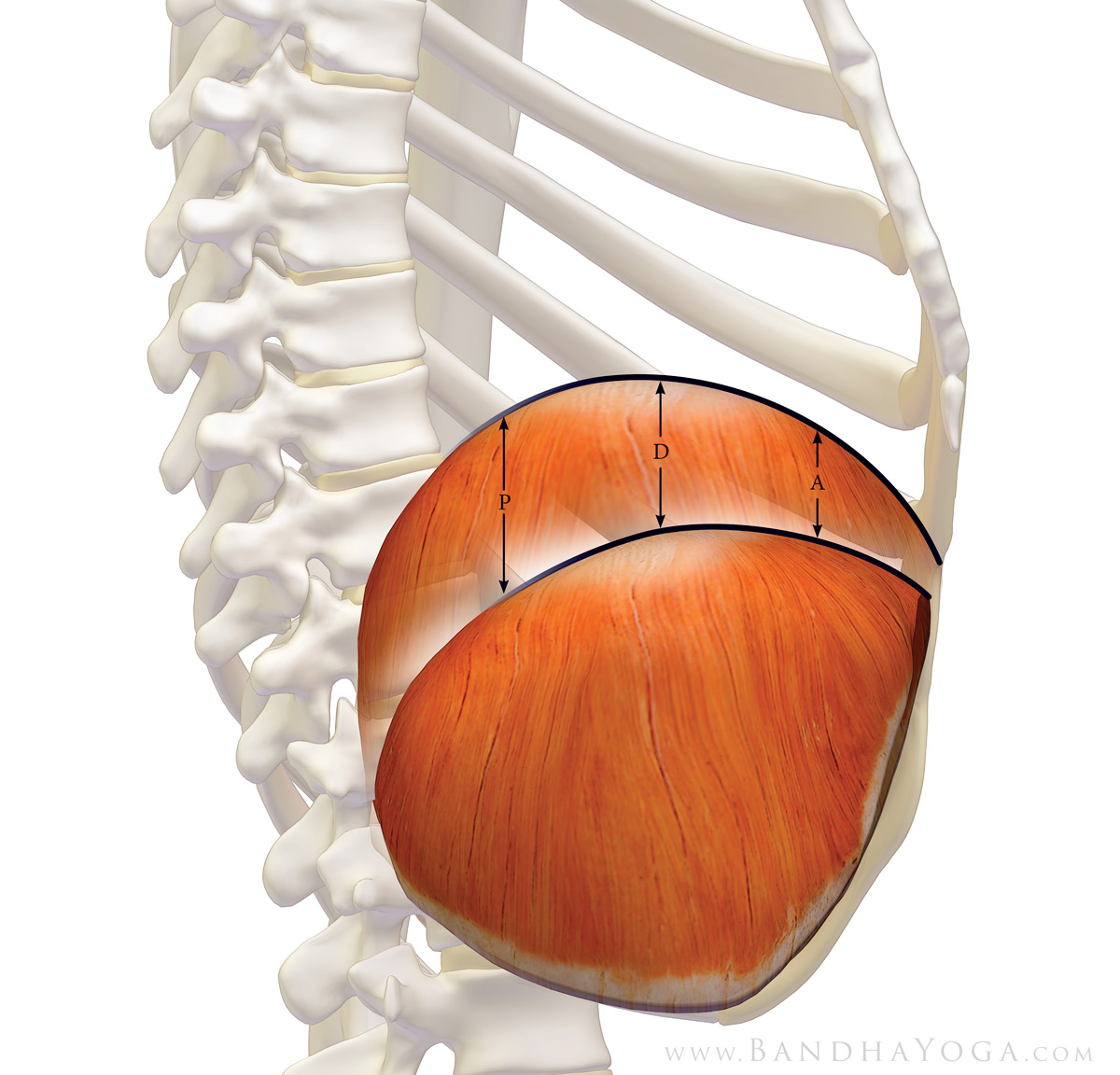

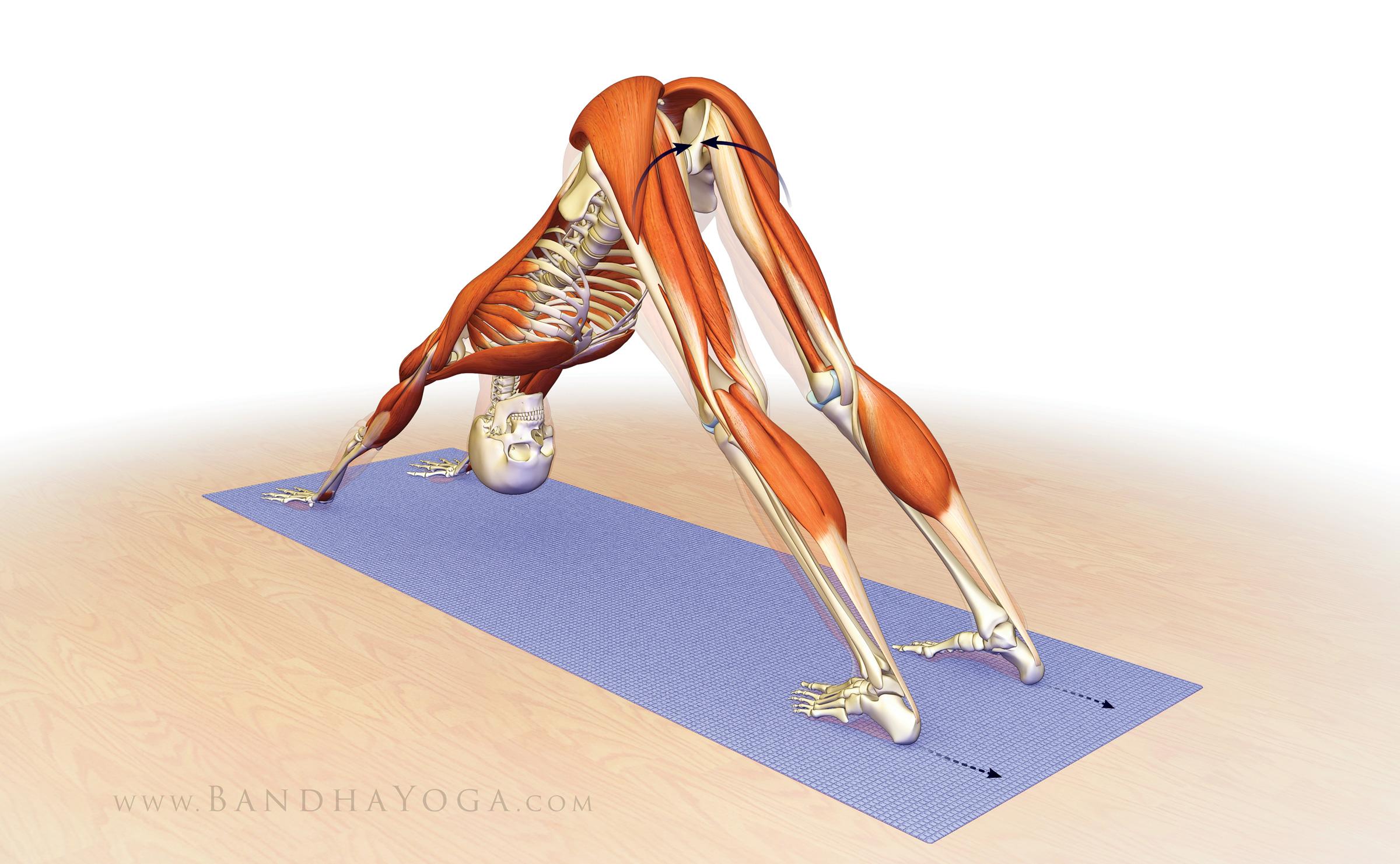

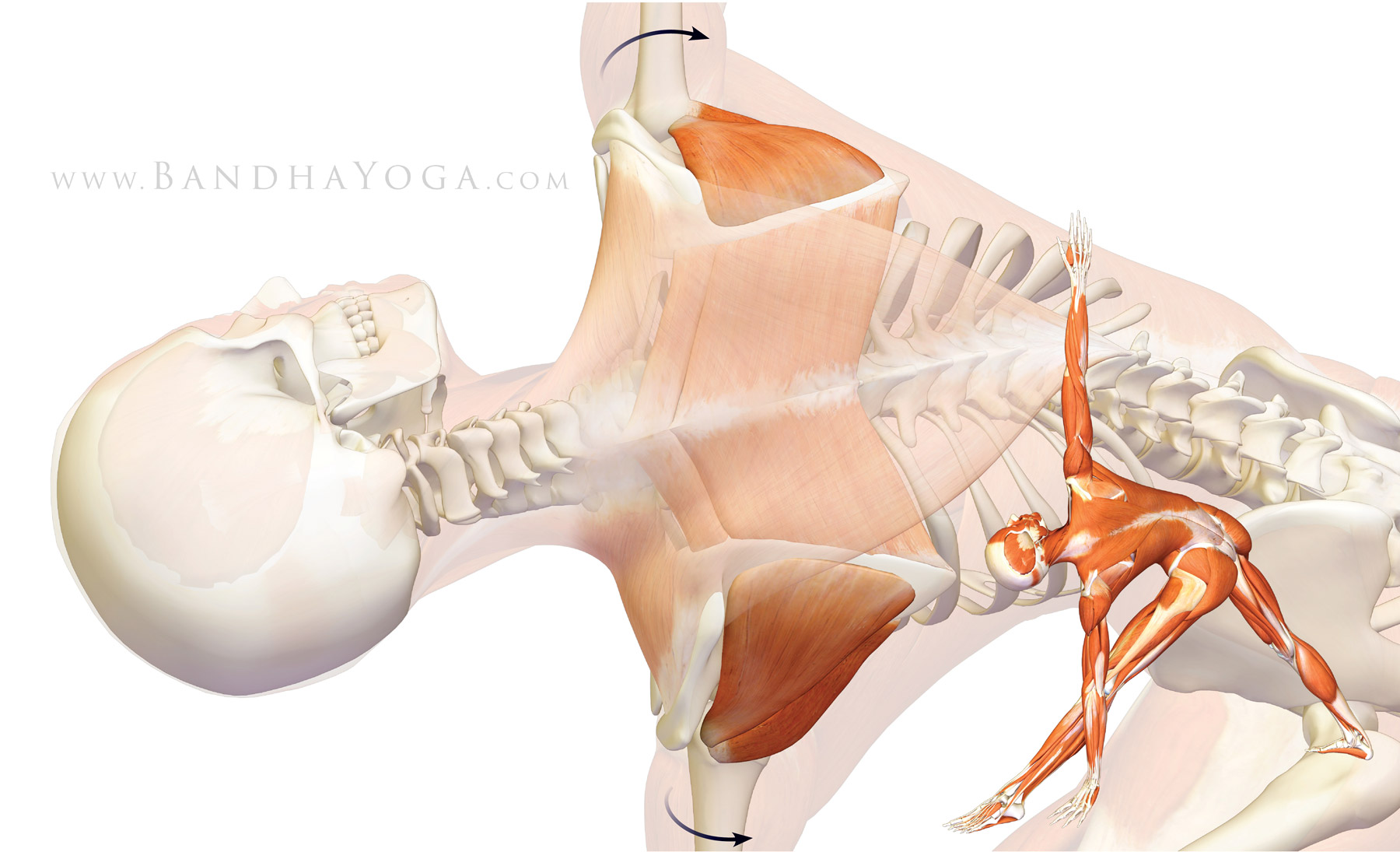

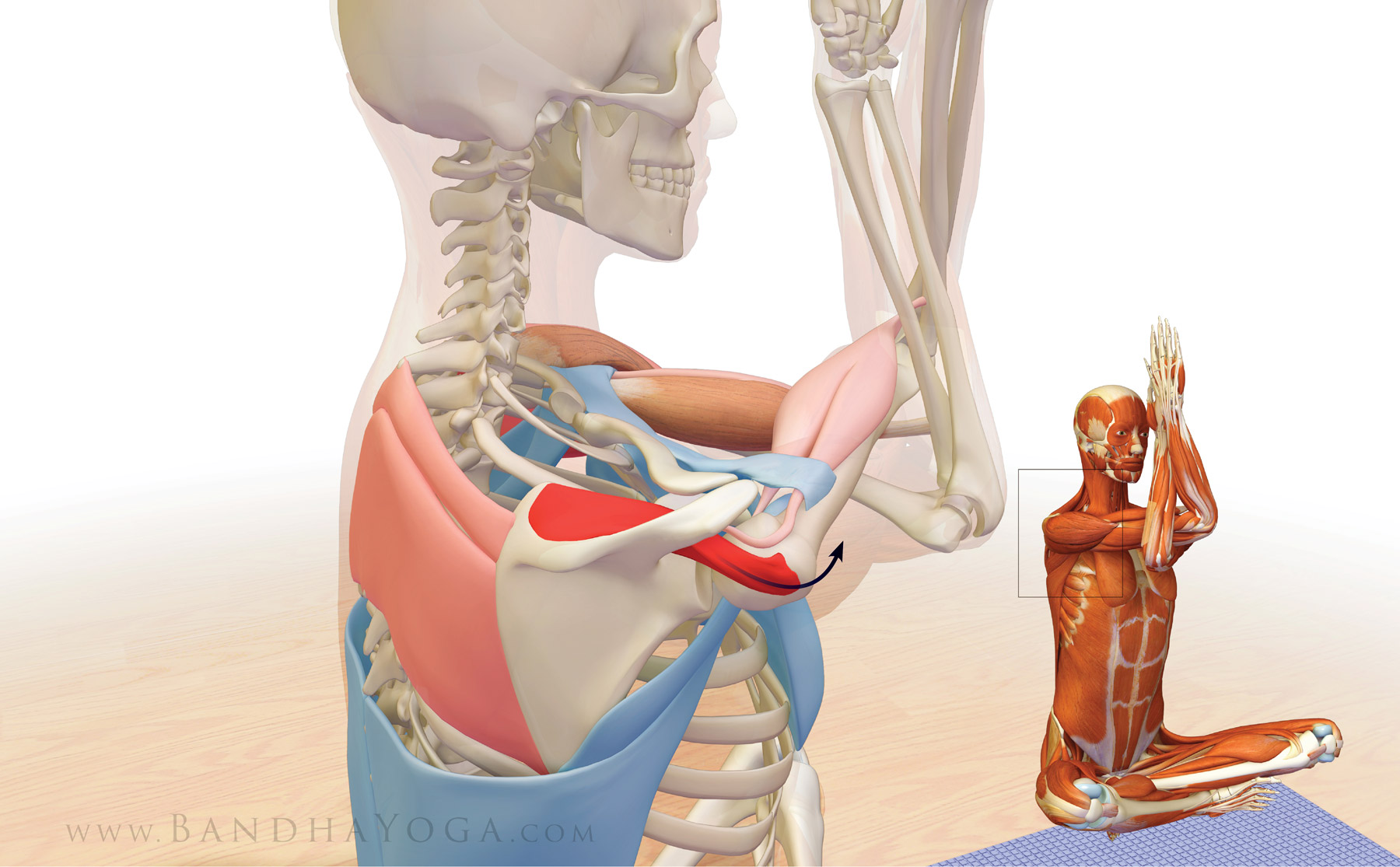

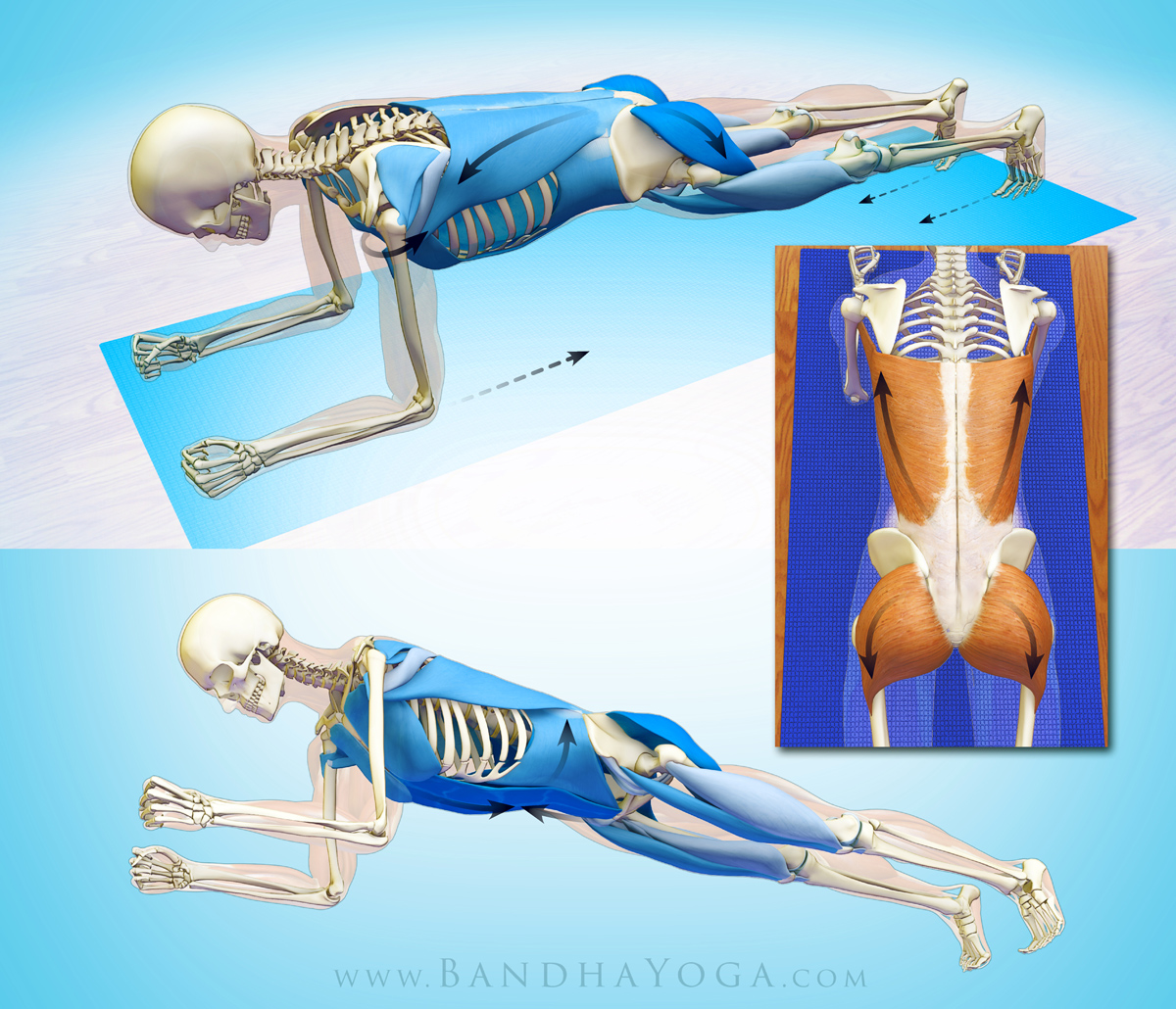

Figure 4 shows a couple of page spreads from our Yoga Mat Companion book series, illustrating a step-wise approach to working with muscle engagement in the poses.

![]() |

| An excerpt from "Yoga Mat Companion 1 - Vinyasa Flow and Standing Poses". |

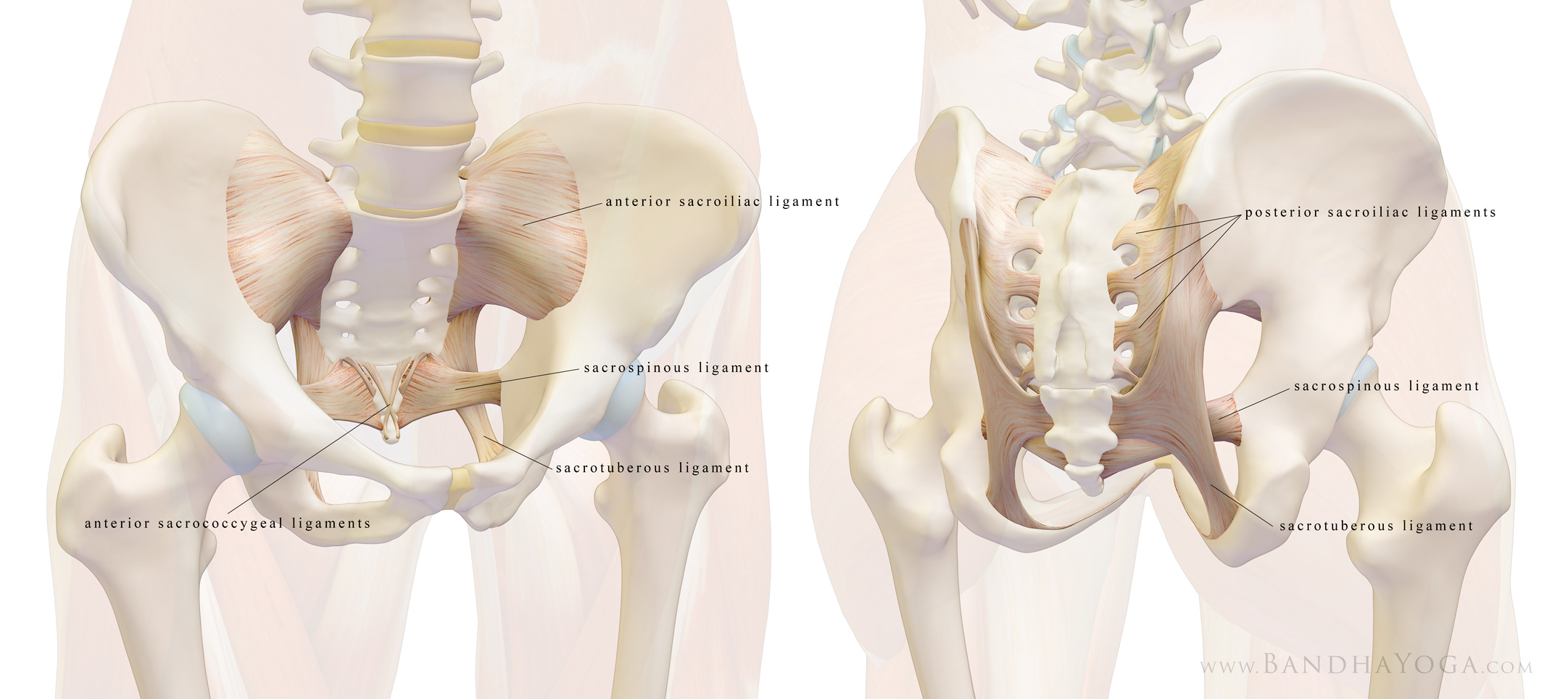

![]() |

| An excerpt from "Yoga Mat Companion 2 - Hip Openers and Forward Bends". |

NB: Evidence based medicine ranks publications and studies according to “levels of evidence”. Level I studies are considered to be more reliable, and are based on randomized controlled trials. Level VII evidence, on the other hand, is essentially an opinion, with variable reliability depending on the source and their actual expertise. The study on active vs. passive stretching I referenced above was a randomized controlled trial (RCT), and is thus Level I(b) evidence.

Thanks for checking in!

Click here for more information on combining modern Western science and your yoga. Hope to see you soon.

Namaste'

Ray and Chris

References- Lavoie BA, Devanne H, Capaday C. “Differential control of reciprocal inhibition during walking versus postural and voluntary motor tasks in humans.” J Neurophysiol. 1997 Jul;78(1):429-38.

- Hortobágyi T, del Olmo MF, Rothwell JC. “Age reduces cortical reciprocal inhibition in humans.” Exp Brain Res. 2006 May;171(3):322-9.

- S. Meunier , S. Pol , J. L. Houeto , M. Vidailhet “Abnormal reciprocal inhibition between antagonist muscles in Parkinson's disease” Brain. 2000 May;123 ( Pt 5):1017-26.

- A. J. Blazevich , A. D. Kay , C. Waugh , F. Fath , S. Miller , D. Cannavan “Plantarflexor stretch training increases reciprocal inhibition measured during voluntary dorsiflexion” Journal of Neurophysiology Published 1 January 2012 Vol. 107 no. 1, 250-256.

- Meroni R, Cerri CG, Lanzarini C, Barindelli G, Morte GD, Gessaga V, Cesana GC, De Vito G. “Comparison of active stretching technique and static stretching technique on hamstring flexibility.” Clin J Sport Med. 2010 Jan;20(1):8-14.

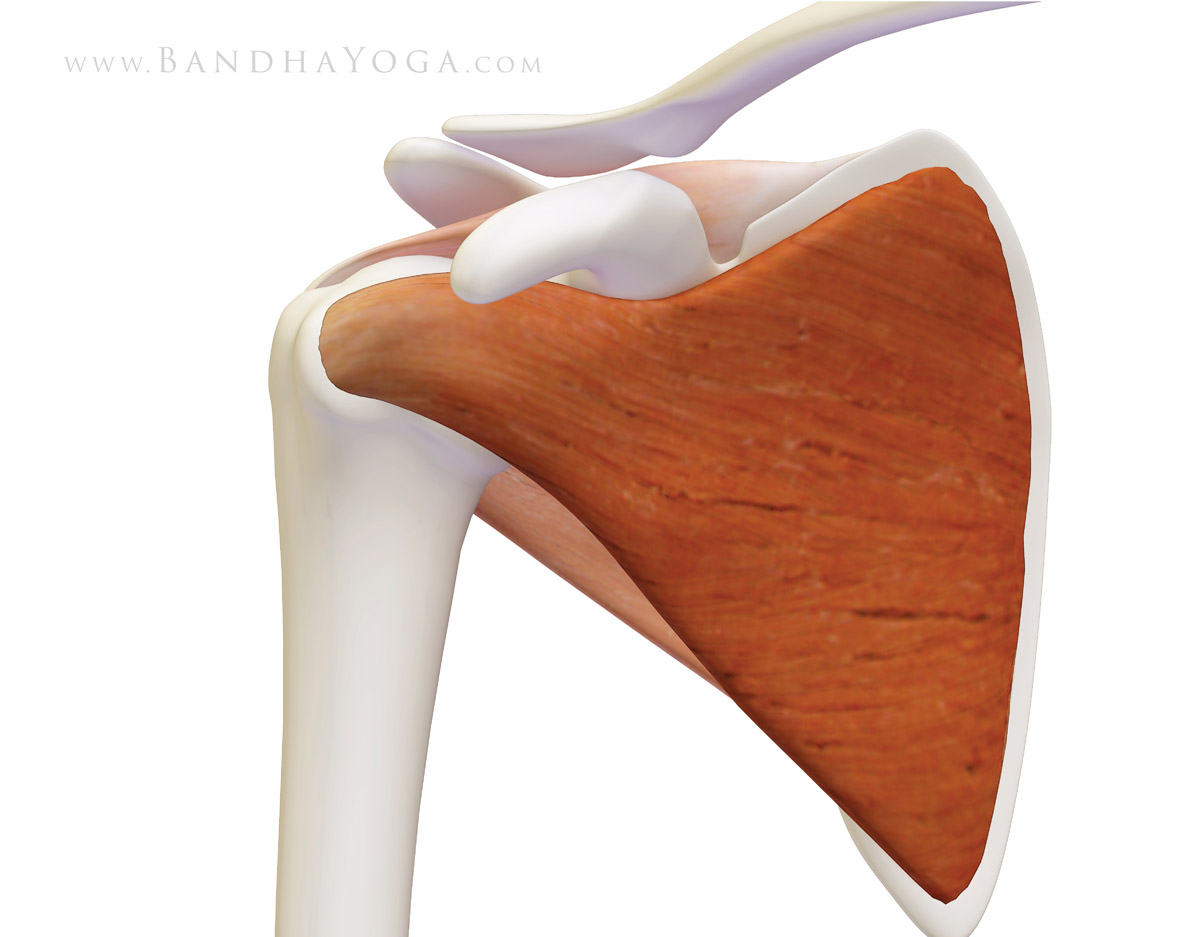

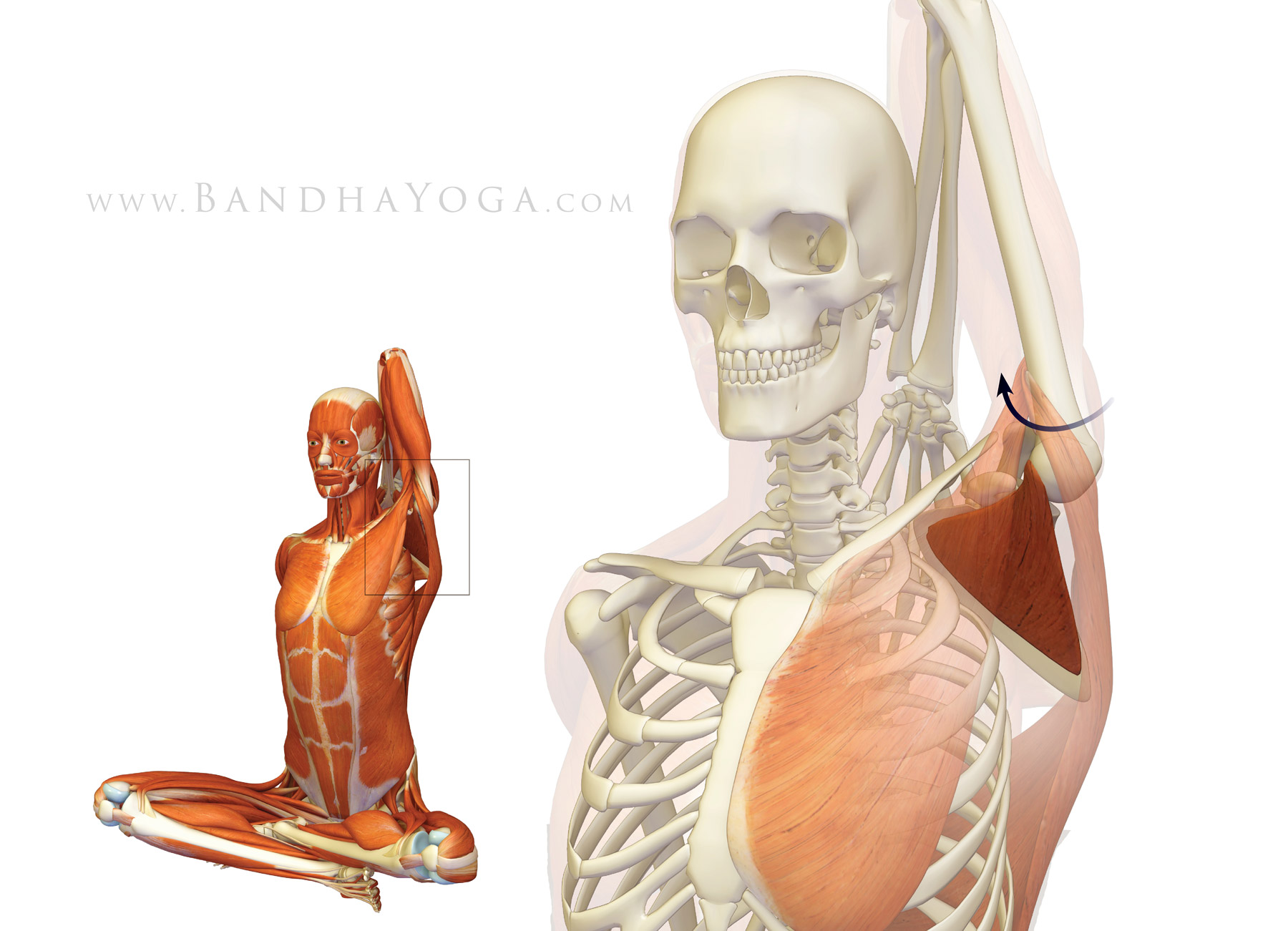

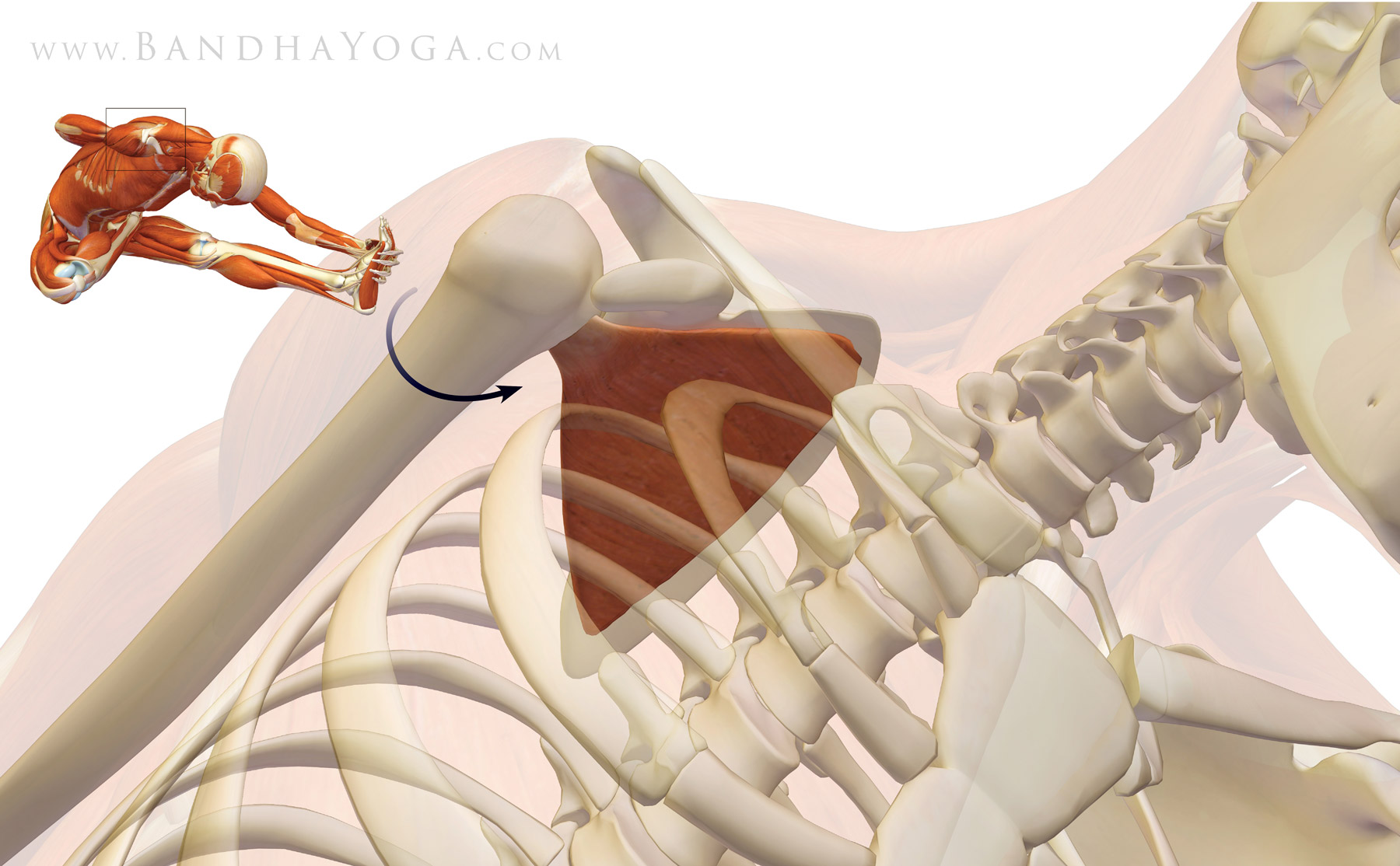

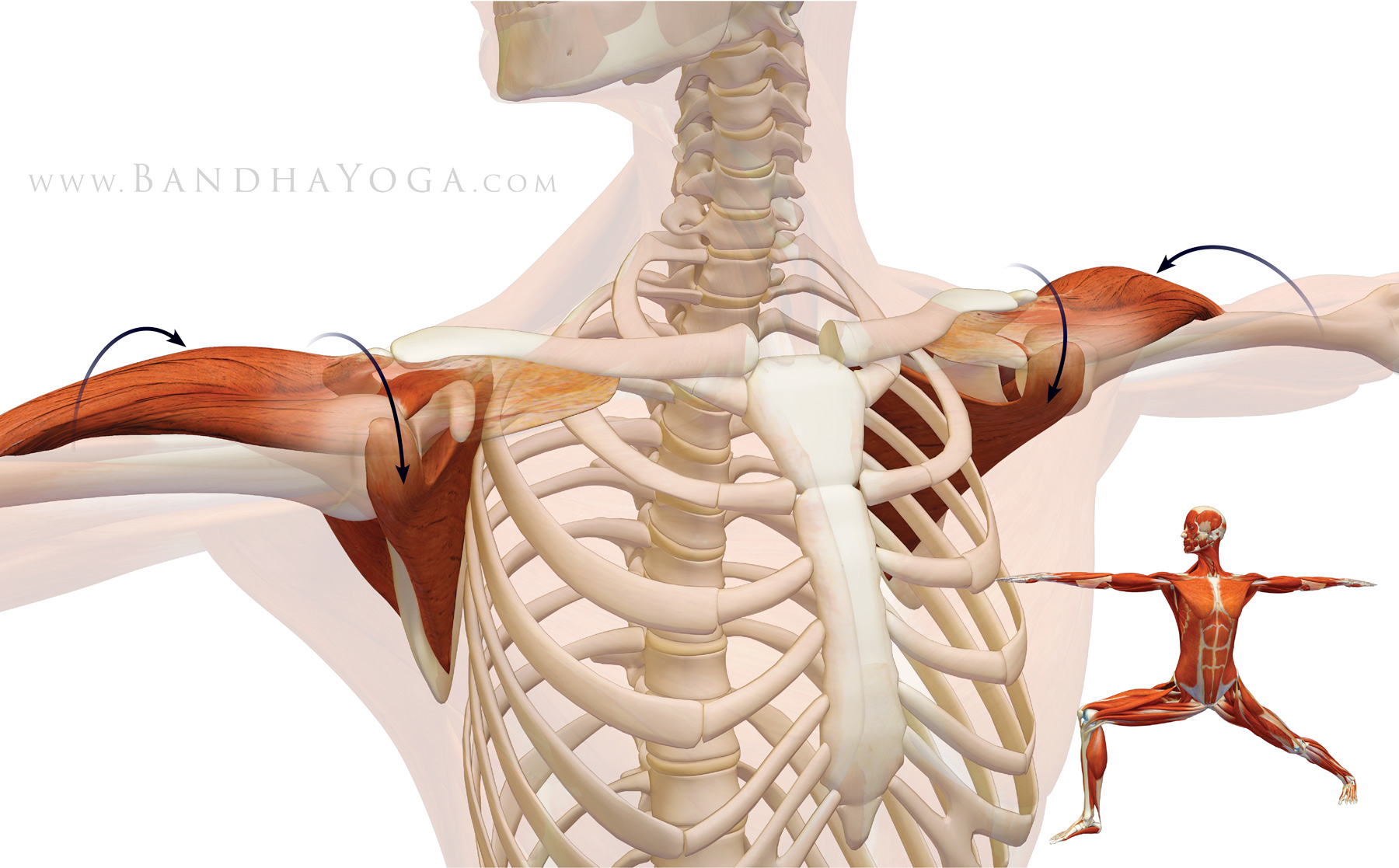

Your Rotator Cuff

Your Rotator Cuff Your Piriformis Muscle

Your Piriformis Muscle Downward Facing Dog Pose

Downward Facing Dog Pose